Cybersigilism: the Forever Trend

|CASSIDY GEORGE

At some point in the late 2010s, it started growing like a weed in the dark corners of the Berlin club scene: a style of blackwork tattooing that fuses ancient looking symbols with digital aesthetics. “Cybersigilism,” as some call it, is difficult to describe, but easy to identify.

(Side note: If you don't want to commit to a permanent tattoo, buy our 032c temporary tattoos HERE.)

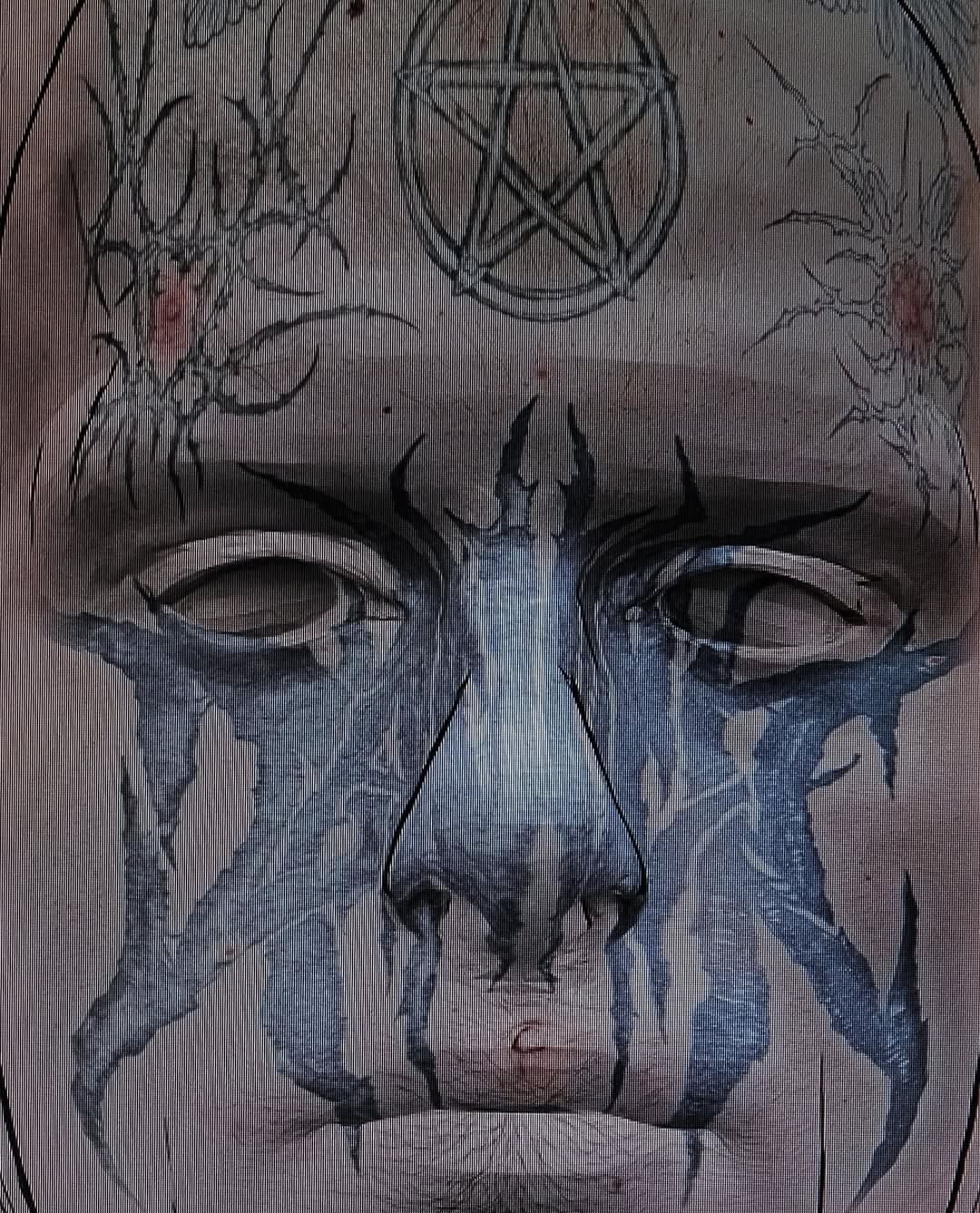

Design by cybersigilism

Drawing on the visual languages of HR Giger and the logos of metal bands (particularly those designed by Christophe Szpajdel), the spiderweb-like aesthetic fuses hints of cyberpunk and futurism with seemingly mystical amulets. Often, the designs look like alien vascular networks or Art Nouveau electrical currents, while appearing both organic and mechanical simultaneously. “I’ve seen people say it looks like a witch’s curse,” said Aingelblood, a tattoo artist from LA who goes by @cybersigilism on Instagram. “And honestly, I love that metaphor.” But then there are others who refer to it in more layman’s terms: Gen Z tribal.

Part of the appeal of the broad range of artwork and designs that have been cast under the umbrella of “cybersigilism” is its somewhat cursed aura. The popularity of this tattoo style exploded in accordance with a widespread reaction against older Millennial’s move toward minimalism and cleanliness. Cybersigilism was just an inky extension of a new generation’s graphic rebellion, which meant embracing maximalist, chaotic and “trashy” Y2K aesthetics.

While some cybersigilist works are completely non-figurative, others incorporate Middle-school-friendly icons (hearts, stars, wings, crosses, etc.) and look like updated Ed Hardy t-shirts graphics that can never be taken off.

In the early 2020s, I started seeing the varicose vein-like inkwork being used as a techno tribe member card far beyond the reaches of Berlin’s club queues and bathroom stalls. Its cousins appeared on the runways of brands like Vetements and Balenciaga, and the designs of their impersonators soon made their way into High Street fast fashion. The whispers that were visible in the merch of groups like Drain Gang, Sad Boys, and Haunted Mound became screams in the loud, cybersigilist designs of mainstream rappers like Playboi Carti and Ken Carson. And then when Billie Eilish, Phoebe Bridgers, and Grimes proudly shared photos of their back tats, hip tats, and “alien scars,” it officially went “pop.” As an unexpected link between Gvasalia acolytes, trans artist communities, and suburban Soundcloud lovers, it eventually became evident that cybersigilism would be remembered as one of the defining aesthetics of the plague and recession years.

Design by cybersigilism

II.

To get a sense of what cybersigilism is (there is only murky consensus), what type of meaning it holds for people, and what might come after it, I spoke to a collection of artists and experts.

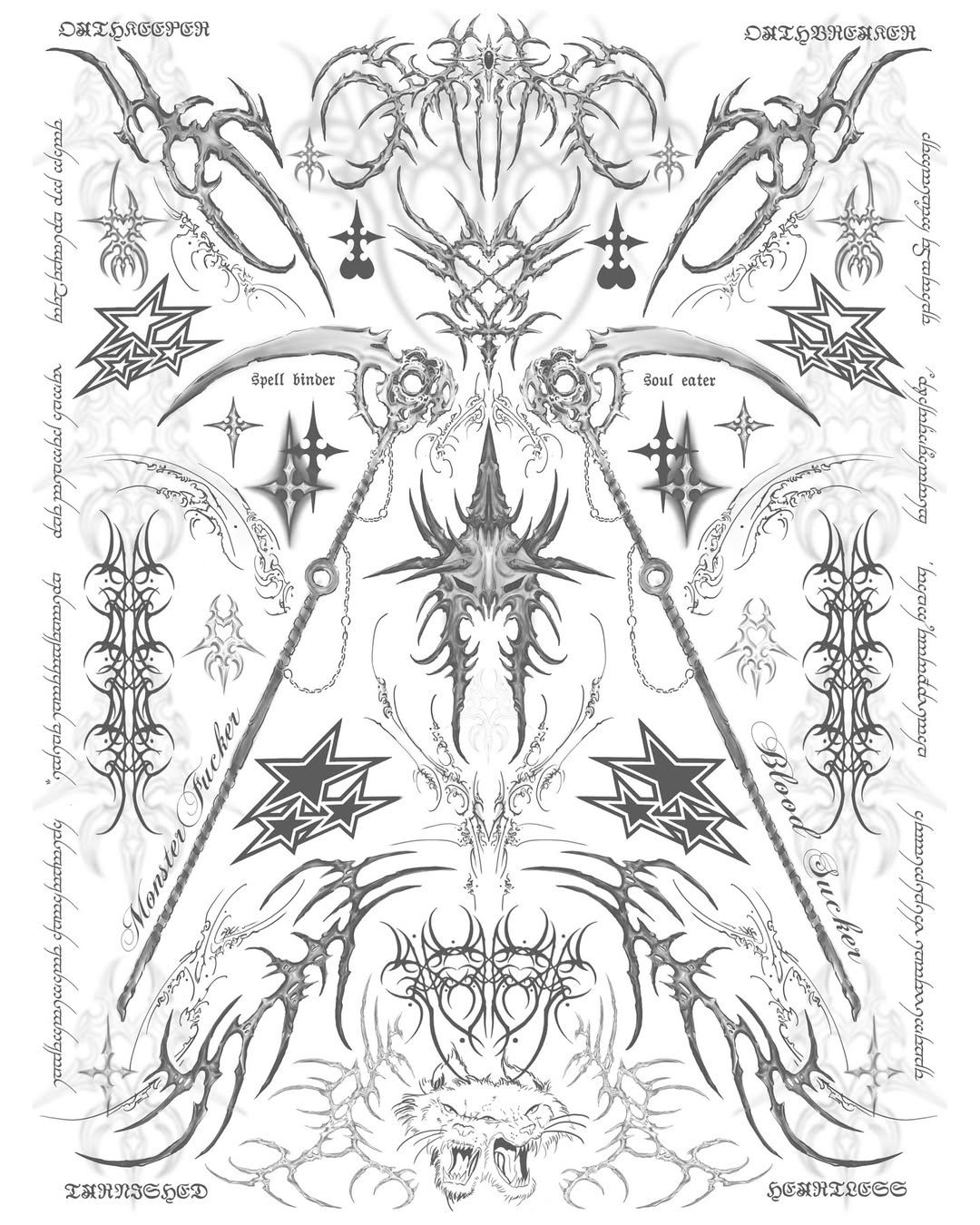

LEFT: Design by christophe.szpajdel

CENTER: Ken Carson merchandise

RIGHT: Bladee for "Narcissist" cut & sew collection by Playboi Carti

DR. KIMBERLY BALTZER-JARAY

Professor of philosophy and tattoo scholar, Ontario

CASSIDY GEORGE: How do you understand “cybersigilism” in relation to its philosophical and historical context?

KIMBERLY BALTZER-JARAY: This is a trend that is usually identified with Gen Z, and I would say that means it is situated in their experience of living in an ever-growing cyber reality and surviving in a rather bleak world of economic hardship, war, and destructive climate change. And yet, they have a desire to find meaning and connection with something greater than themselves and express it on their flesh. It is interesting to think that the more digitally connected we have become the more untethered and isolated many people feel. Sometimes, this explains interest in ancient symbols, spirituality, and old art practices. It can help make someone feel connected to an element of humanity that has roots.

For me, cybersigilism is an evolved idea of the biomechanical but one that has a heavy focus

on a more simple, black, fine-line style. Because art is intimately part of culture, this makes sense. The twentieth century was preoccupied with mechanization—not only in the two world wars that saw machines replace animals and armor, but we saw labor become far more mechanized, our households too, and even our bodies with replacement parts and pacemakers. In the twenty-first century, the cyber has replaced the mechanical as something that is integrating with and changing human life, and is also now fearsome—the focus is less on the physical robot itself rising up and taking over, and more squarely the idea that AI can become sentient and at some point out think us. [Cybersigilism] is a natural evolution that is mimicking the society we live in—at least in the West—and what our preoccupations are.

CG: Some people call this trend “Gen Z tribal.” Does this bear any resemblance to those tattooing traditions?

KB: Using tattoos as signs to your community is an ancient practice. There are, for example, many Indigenous peoples globally who have practices for women that coincide with first menstruation; and so, once the tattoo is done—in many cases on the face, but they can occur on the body—her community knows she is an adult and ready for marriage. In other cultures, tattoos serve as an amulet—another super old tradition—where number, figure, and placement is meant to protect the wearer to bring luck, thus communication with gods and or the universe itself.

On the spiritual side, I see influences from traditional ancient sources, such as Norse and Celtic—Gaul, Briton, and Gael—patterns, letters, and symbols. We can also look at mandalas too. And, in its use of the 90s style called “tribal,” we can identify tattoo patterns or shapes of the Indigenous peoples of Borneo, Aotearoa, Polynesia, and Micronesia.

CG: Is this a form of cultural appropriation?

KB: As a researcher of tattoo history and culture, my position is that tattooing as a practice in

Western, predominantly European, white culture is largely cultural appropriation. There is no

escape from this—even with a fancy name that sounds fresh, abstract, and shiny. New labels and line styles do not negate that putting ink into skin is a practice taken over from other peoples, often ones that were colonized or encountered violently during expedition. In fact, I would argue that to try to deny any connection to or distance from the fact tattooing is appropriated from ancient Indigenous peoples is disrespectful and inappropriate.

When I look at examples of the style, it is easily identifiable as a new version of “tribal” tattoo style. The truth is a lot of Western culture is cultural appropriation from colonization and imperialism—spices, farming techniques, textiles, math. Tattooing is no different.

YATZIL RAMIREZ

Tattoo artist and visual artist, Mexico City

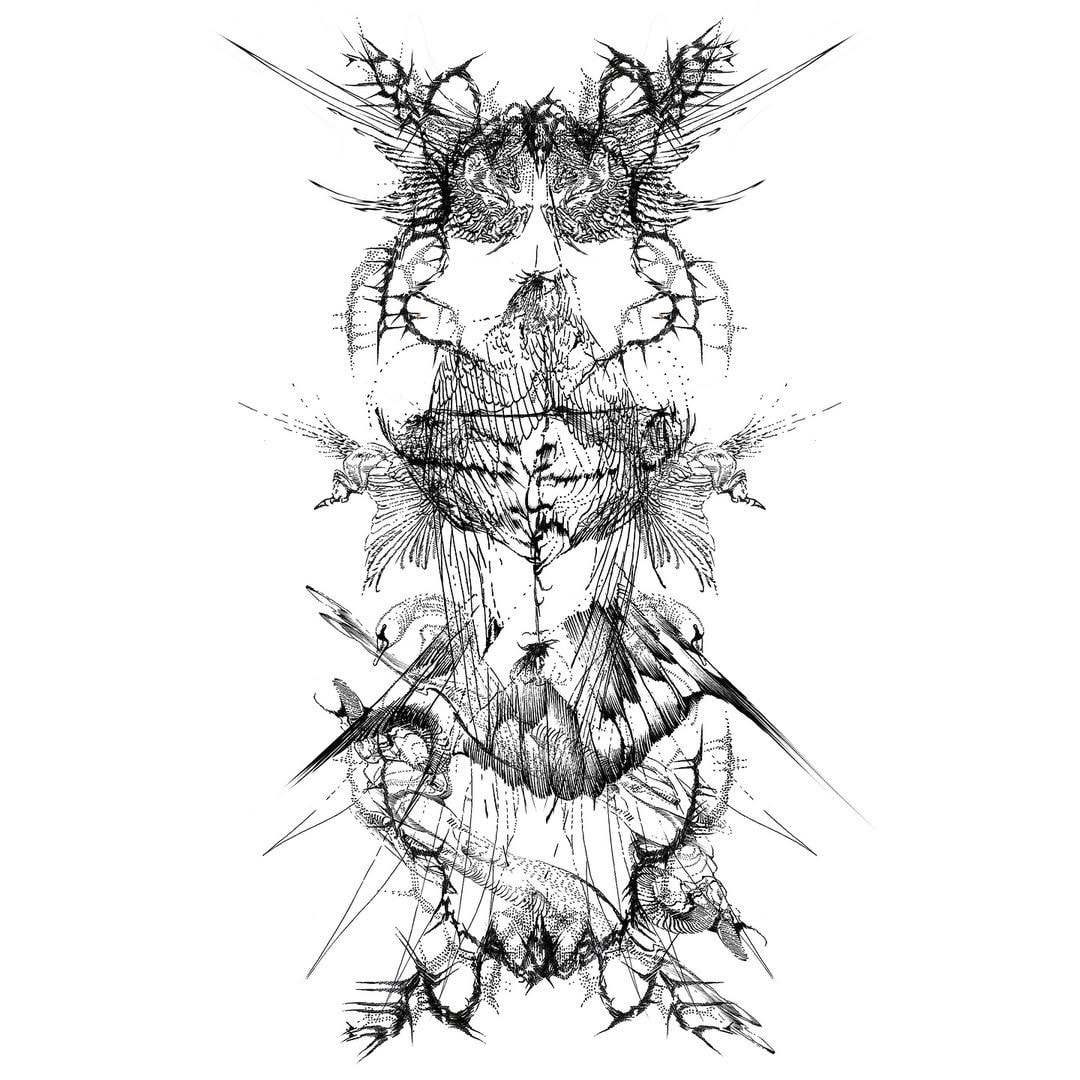

Design by Yatzil Ramirez

CG: How would you describe your clientele?

Yatzil Ramirez: Many are people with similar tastes in music and audiovisual culture, such as punk, anime, comic books, manga, vampires, and dark surrealism. Many have also experienced some type of adversity or spiritual miracles. In many cases, they are members of the LGBTQ community.

CG: Do you identify with the word “cybersigilism”?

YR: People who search for me often ask me what name I give [my work], but the adjectives I use refer specifically to each composition. Some of the terms I use are “entropy demons,” “energy weapons,” “devouring armors,” “aberrations,” and “soul devices.”

Cybersigilism does not refer to technology but to magic. When I create sigils, I try to do it from my subconscious—like a strange language. I didn’t start this with a preconceived idea of where it would lead, it was just an attempt to represent emotions and ideas or dreamlike experiences—also concepts like entropy and spirituality. I was never trying to create a futuristic aesthetic. I think what I do is timeless.

CG: Why do you think it has become so popular?

YR: There are more and more people making designs of this style because many people now have access to new tools such as AI generators or tablets with symmetrical drawing assistants. It’s easy to do. In most cases, it seems to be a sign of opportunism.

AINGELBLOOD

Tattoo artist and visual artist, Los Angeles

Design by cybersigilism

CG: Your tattoo account handle is @cybersigilism. Why did you choose to specialize in this style?

Aingelblood: This particular style was not around when I first started tattooing, but the aesthetic has been around since the early 2000s, mainly in video game culture. My motivation was basically to create designs and symbols that stray from the realm of traditional American tattooing, and that felt very meditative and intentional. The term “cybersiglism” came from a passion project of mine for a style that was more about bodily autonomy and reclaiming one’s worth through magical symbols and ornamental shapes.

CG: Do you think most of your clientele are interested in it purely for visual reasons? Or do these designs hold deeper meaning to them?

A: Cybersigilism absolutely holds greater meaning to me and my clients. I started focusing on this full time as I started transitioning, so I feel like I embody it. I’m also able to do that for a lot of other trans clients who don’t necessarily feel comfortable in traditional tattoo spaces. I take a lot of pride in being able to rewrite tattooing for those people. [For a long time] in America, a lot of tattooing was so cut and paste. Now we’re seeing a lot of DIY tattooing takeoff and thrive.

CG: How do you feel about the term “neo-tribal”?

A: I personally do not resonate with the term. A lot of tattooing comes from Indigenous cultures. The least we can do is let “tribal tattooing” be reserved for the cultures that have long been doing this with meaning, which differs from more abstract or ornamental art such as cybersigilism.

GIULIANO BOLIVAR

Tattoo artist and visual artist, Amsterdam

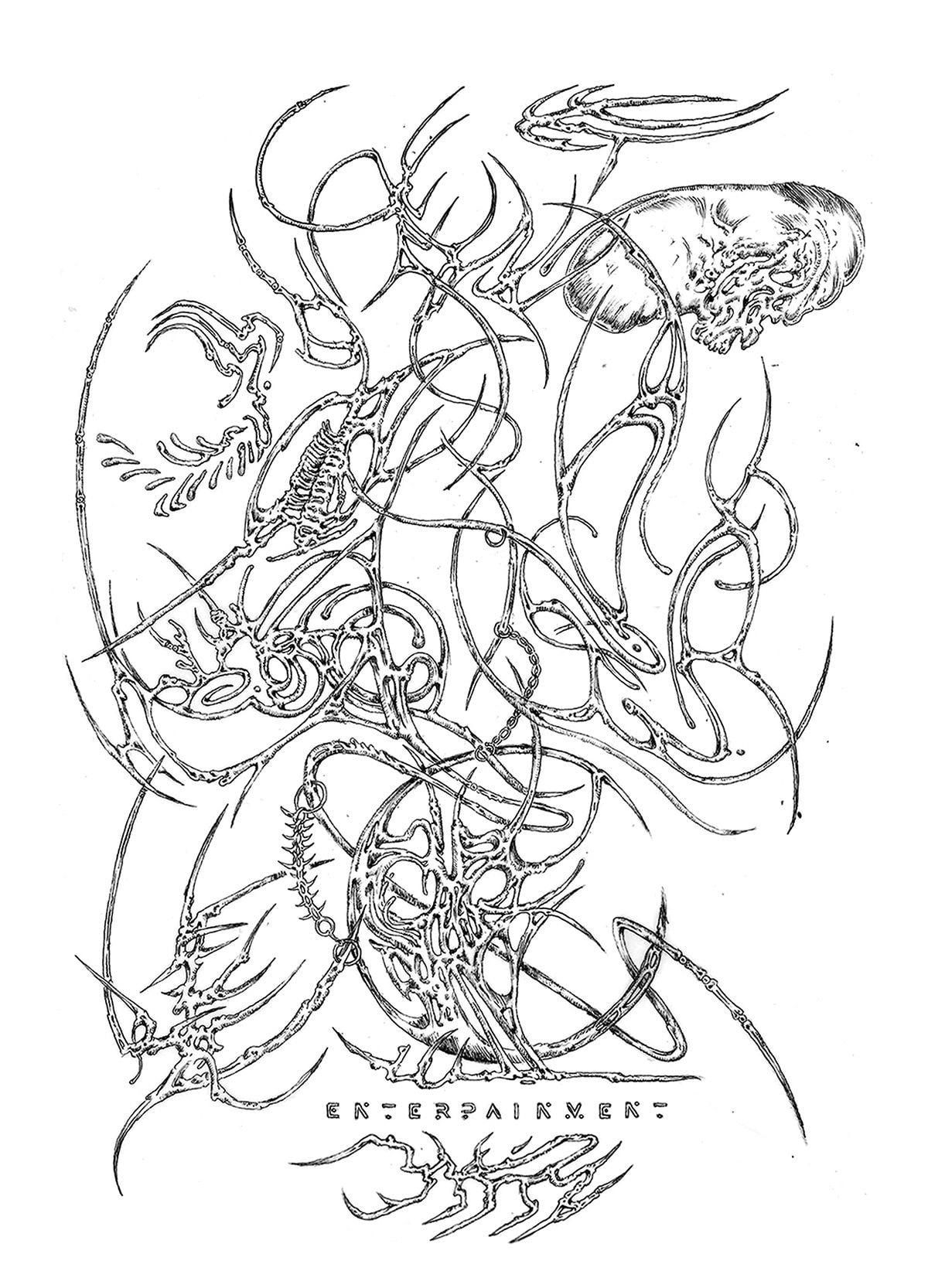

Design by hhholy.hq

CG: What sort of connotations do you have with these kinds of designs?

GIULIANO BOLIVAR: When I noticed everyone getting this type of tattoo, I said right away: this is not going to age well! In my mind, it’s very linked to subculture and club culture. It’s very techno, it’s very rave. Anytime I made designs that were close to this style, the kinds of kids showing up to get tattoos were wearing their Buffalos.

It makes a lot of sense to me, though. At clubs, people wear very little clothing and everyone has tattoos. In the culture around certain clubs, everyone wants to look the part. This desire for more local belonging then bled into high fashion because Vetements did it, and then smaller hype brands copied them. Once rappers started wearing it, it gained a much longer lifetime—and a far more profitable one.

CG: You participated in an exhibition called “Post-Tribal” at the Design Museum den Bosch. Can your work also be understood as a proposal for what might come after cybersigilism?

GB: A lot of tattoo artists started working in this realm and then made their way into new territory. I think this is especially true of artists in the queer community, who I have noticed are moving into more poetic looking styles. They’re doing things that are softer and more abstract, which resonates more with queerness, in my opinion. In the straight male world, the style has only gotten stronger and harsher.

I like to think of what I do as alien angel whispers. I draw a lot of inspiration from tropical flowers, exotic animals, and insects. I typically layer these with unfinished sketches of classic paintings and then create a mixture of art, nature, and machine by layering these references and then deep frying them. When I yank up the brightness and contrast, and then print it out, retrace, scan, liquefy, and print it again, suddenly these angelic looking things that are fragmented and falling apart appear—things that seem to be floating in space.

JUMI SU

Tattoo artist and visual artist, Berlin

Design by jumi_su

CG: Maybe I’m biased, but I feel like Berlin is the mecca of this trend. You’re also based in Berlin—is that fair to say?

JS: Absolutely. Berlin is the perfect ecosystem for it. The city thrives on tension—between tradition and experimentation, rawness and refinement, the underground and the mainstream. This aesthetic fits into that narrative seamlessly. That said, it’s not just Berlin. Cities like Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Kyiv, New York, and LA, to name a few, are pushing these ideas forward in their own ways.

CG: What do you think the ubiquity of this look says about the zeitgeist?

JS: This aesthetic is a reflection of our collective grappling with the omnipresence of technology and a need for more traditional values, which is reflected in the fusion between religious symbols and other overlapping tokens. It’s collaging different images and cultural, mystical objects to blend it to absurd imagery. Post-post-post modernism, everything’s a remix. It acknowledges imperfection, vulnerability, and identity in a hyper-curated world. The popularity of this style—both in tattooing and in graphic design—speaks to a desire for connection and meaning amid digital overload.

CG: What does “cybersigilism” mean to you?

JS: While it’s not the defining framework of my art, I do understand its implications. It speaks to the collision of mysticism and technology, a kind of visual alchemy for the digital age.

The idea of internet mysticism—crafting sigils or symbols for the virtual era—is compelling, especially when tattooing is inherently about permanence and physicality. For me, the deeper meaning of tattooing lies in its intimacy: the act of engraving another person’s skin and creating a lasting mark in a world where so much is transient. It’s not so much about a particular style than it is about the moment itself.

III.

The more I learned about cybersigilism, the hazier the distinctions between it and everything else became—particularly the design languages that are most similar to it, such as metal graphics. Social media platforms, algorithms, and the rise of clinical websites like Aesthetics Wiki have incentivized us to name, categorize, and hashtag everything under the sun, and this leads us to confuse matters of opinion with objective truths. Even when formal definitions of these terms exist, “Is this cybersigilism?” is as subjective a question as “Does this look surrealist to you?” Most artists whose work is affiliated with the term either never did or no longer identify with it. This is likely due to the newfound, trendy connotations with the word, but also because most artists don't want to be stylistically pigeon-holed—the same way that many of the musicians associated with genres like punk, emo, and hyperpop have rejected (and resented) the terms projected onto them by others.

No matter how subversive a design language is, it can and will supersede the preexisting norm if it gets popular enough. If you search “cybersigilism” on TikTok today, you’ll find videos of tattoo artists naming it as the style they are most sick of. This is where the irony of this phenomenon truly sets in. Trends are trends because they are ephemeral. Tattoos, on the other hand, are forever. Will we see a “witch’s curse” in 2045 the same way we see 90s “tribal” today? Or will cybersigilism transcend its trendiness and become a new classic? Only time—and skin—will tell.

Credits

- Text: CASSIDY GEORGE