GOSHA RUBCHINSKIY: Crimea/Kids

In today's media landscape, a book review is often a slap on the back. A handshake among colleagues that says, “well done.” But we have never been afraid to offer critique when critique is due. In our print section Berlin Reviews, we’ve always tried to take the propositions of a book seriously and push them to their extremes.

Archive Berlin Review from our Issue #27 (2014).

There is a stirring quality to the photographs of teens that fill the pages of Crimea/Kids, Muscovite Gosha Rubchinskiy’s latest fanzine, taken prior to the outbreak of violence in the oil-rich peninsula earlier this year. A protégé of Commes des Garçons, as well as a photographer and filmmaker (032c published an eponymous photozine of his work in 2010), Rubchinskiy has traveled back and forth between Moscow and Crimea since 2011. As Rubchinskiy explains, the intention of his project was never political: “I think it’s important to show people normal life in Crimea, to show the kids and the people, the beautiful places in Crimea.” Nonetheless, the region’s current tension looms over the work like a silent third wheel. Flipping through the pages of Crimea/Kids, one can almost viscerally feel the chasm formed around its vision of normal, teenage life. This past August, in the city that had served as a backdrop for the Rubchinskiy’s skaters only one year before, Vladimir Putin declared Russia’s annexation of Crimea “absolutely legal.”

“Crimea has a unique atmosphere. on the one hand, it is full of the right kind of nostalgia, like in Tarkovsky films; on the other hand, sometimes it looks like LA.”

Crimea is populated by a large majority of ethnic Russians, and Crimea/ Kids reads as a barometer of things to come. Rubchinskiy’s work seeks to document how a generation of net-natives has redefined a national identity, while remaining aware of its heritage. “All these kids were born in a new country, and because of the internet, they feel the same as other young people in London, China, or Japan. That’s why it’s interesting for me to see how these young kids born in an informational context manage to keep this kind of Russian spirit, this Russian view on things.”

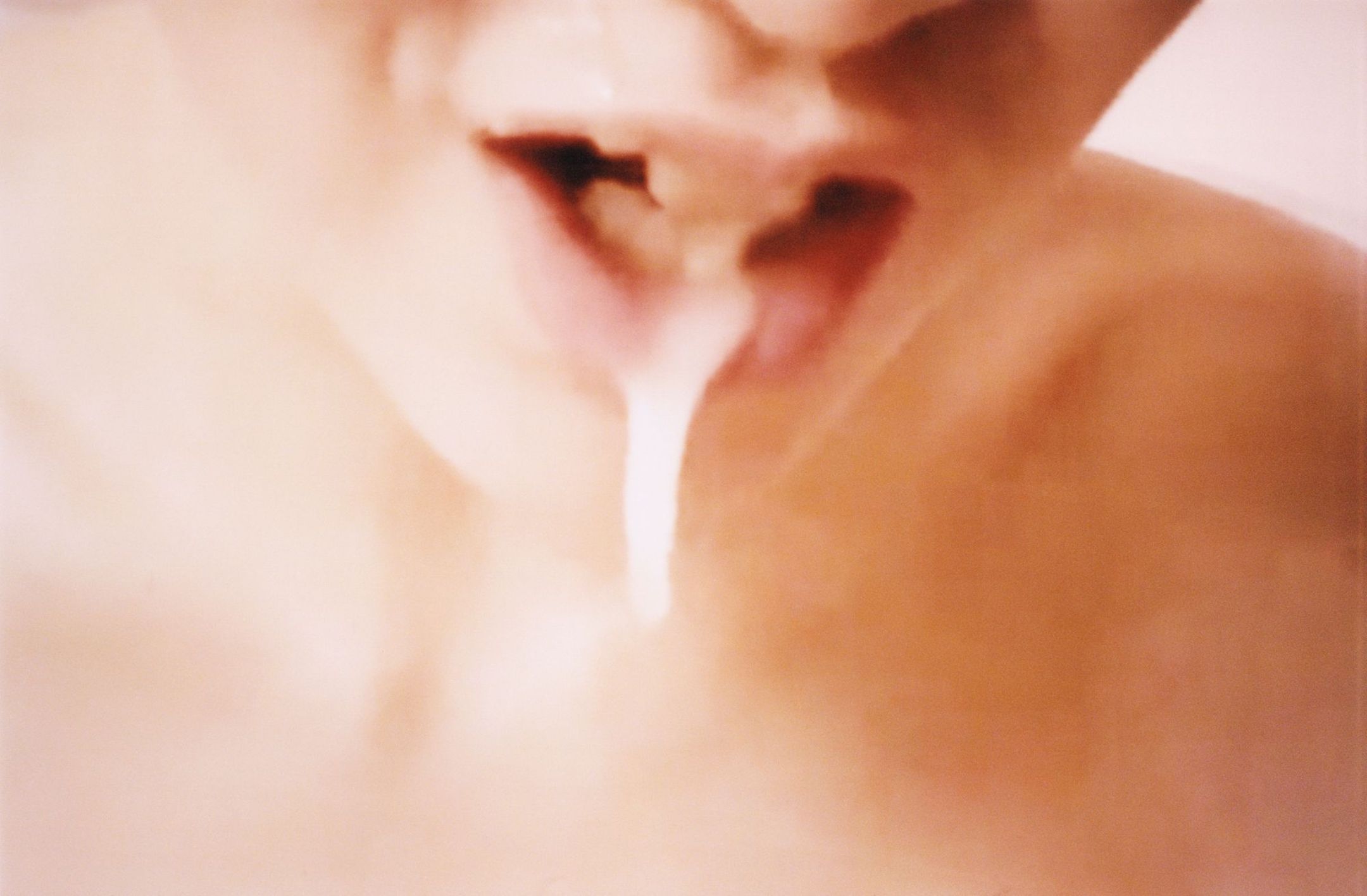

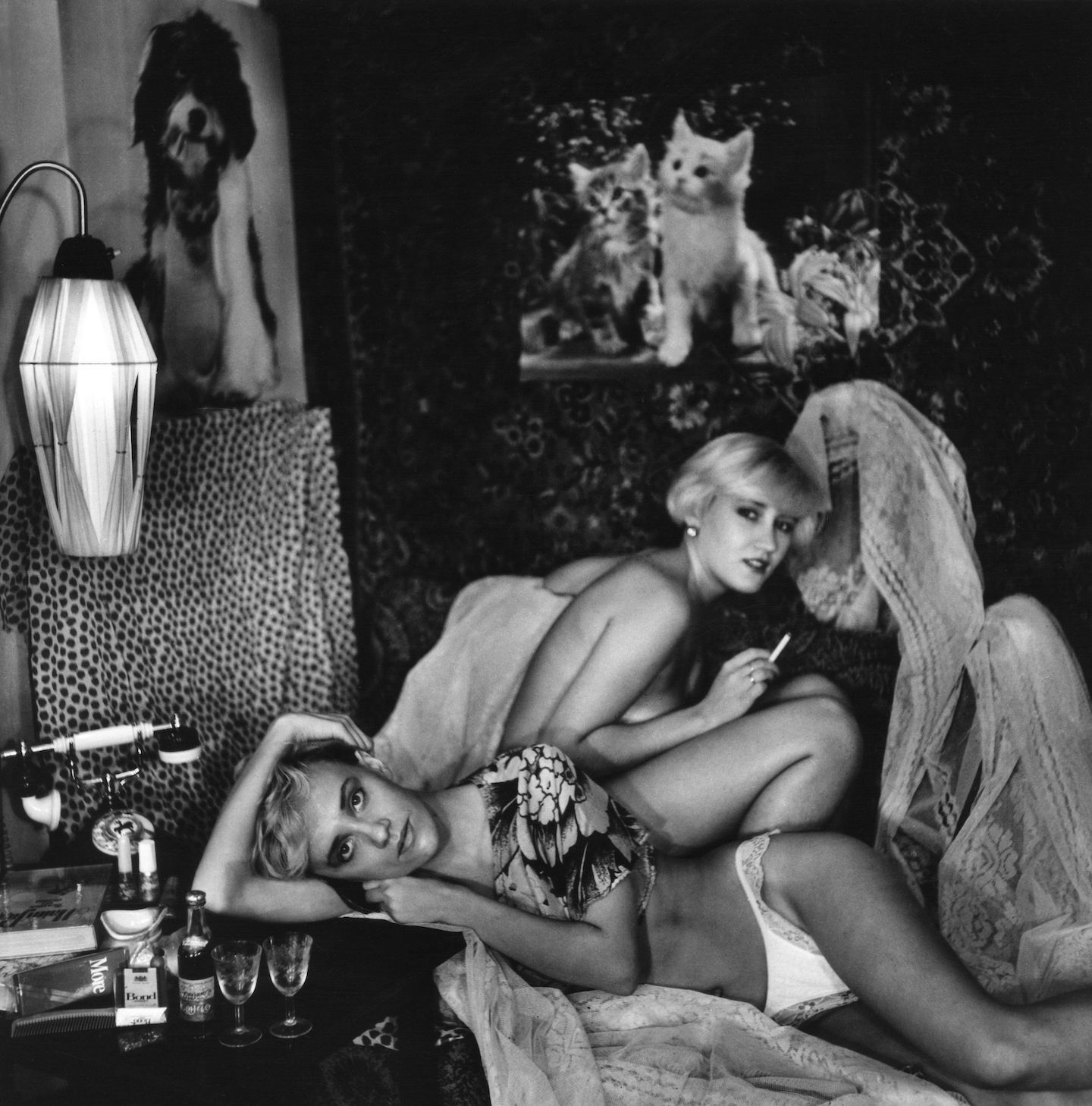

Crimea/Kids depicts skating as a way of navigating this terrain of cultural flux, a connection to a larger, global discourse. Yet Rubchinskiy’s fanzine is far more than a Russian translation of Larry Clark. Juxtaposed with pictures of orthodox iconography and Soviet sculpture, the splendor of youth becomes abstracted from its form. Often, figural poses of flesh find their mirror in inanimate marble, concrete, or cast bronze. A black-and-white shot of a tattooed, shirtless teen offsets two electric pylons jutting into blue sky. Meanwhile, an image of a cactus covered in tufts of yellow spines opposes the portrait of a solemn blonde. When they gaze into the distance, these teens seem to lose their guard, and their faces reveal a tender, open quality that is lost by adulthood. Crimea/Kids operates in the same manner as a religious icon – looking at the photos within transposes us into a moody teenage world of hesitantly articulated desire. It shows that the beauty of youth is perhaps timeless in part because youth itself is not.

Crimea/Kids is published by Idea Books in an edition of 300 (London, 2014).

Related Content

VITALI GELWICH’s Boring Book

True West: KAROLIINA PAATOS’s American Cowboy

TOM McCARTHY Incarnate

WILLIAM T. VOLLMANN: Conflict, Compassion and the Process of Understanding

FRIDA by ISHIUCHI

Sex and Nothingness: SIBERIAN MODERNISM in the Great Eurasian Steppe

TORBJØRN RØDLAND: How Powerful is a Face?

An Internet the Size of a Room: Berlin Review