Radical Disinterest: An Interview With Shanzhai Lyric

|Michael Nardone

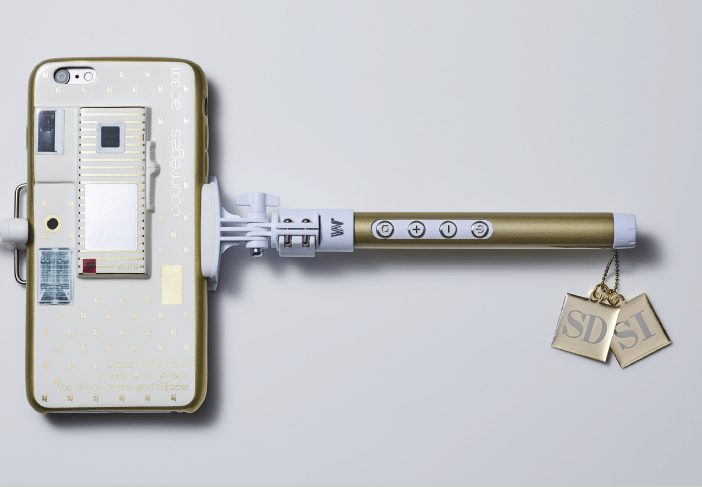

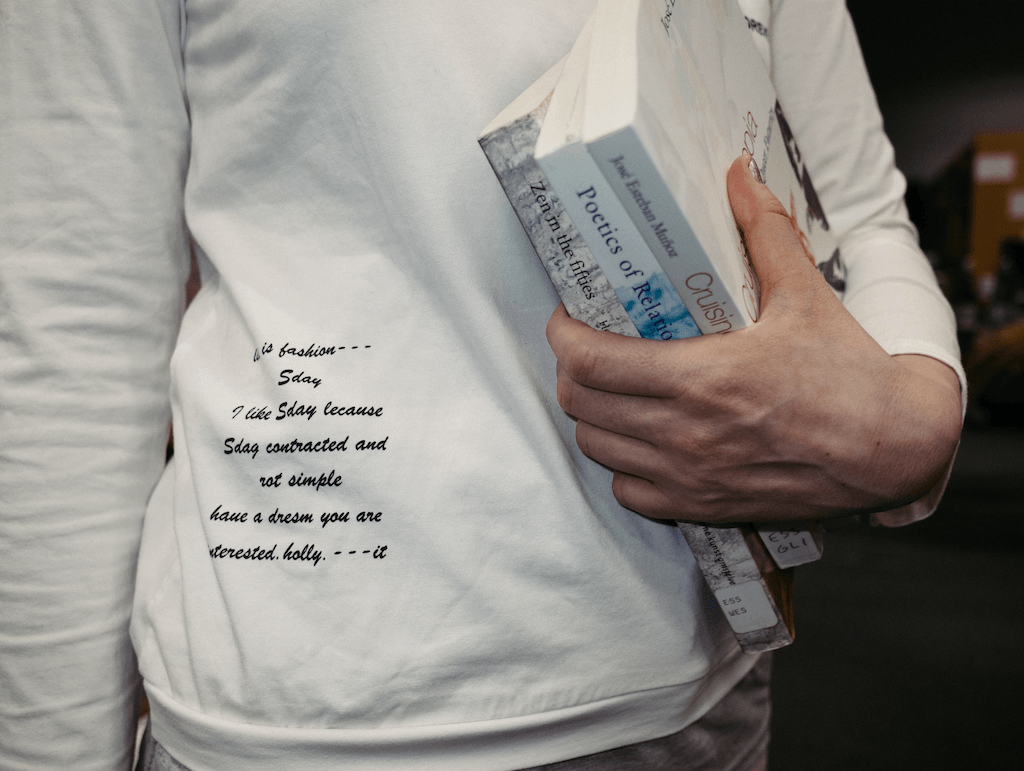

Shanzhai Lyric is a body of research focusing on radical logistics and linguistics through the prism of technological aberration and nonofficial cultures. Initiated by Ming Lin and Alex Tatarsky, the project takes inspiration from the experimental English of shanzhai t-shirts made in China and proliferating across the globe to examine how the language of counterfeit uses mimicry, hybridity, and permutation to both revel in and reveal the artifice of global hierarchies. Through an ever-growing archive of poetry-garments, Shanzhai Lyric explores the potential of mistranslation and nonsense as utopian world-making (breaking) and has previously taken the form of poetry-lecture, essay, and installation.

Michael Nardone: What initially drew you toward these shanzhai garments and their language? How did that evolve into the initial stages of the Shanzhai Lyric project?

Shanzhai Lyric: Ming was living in Hong Kong, documenting errant architectures. Hong Kong, being at the base of China, receives the bulk of mass-produced Chinese goods that filter through it before being distributed all over the world. As a result, there are lots of informal markets pawning off of its excesses, and shanzhai shirts are one of the things that you frequently see. There are whole street markets dedicated to secondary or tertiary markets of those shirts.

Simultaneously, Alex had been thinking about spambot poetry, and about multilingual translation and the translation of apparent nonsense, specifically in the Soviet-Jewish context of diasporic peoples who may not have access to an “original” tongue or mother tongue, so instead they write in an imagined or invented mother tongue. How do you translate a language that is made up and that is collaged of references or desires or intense longings to communicate? The things we both had been thinking about came together in this exciting way through the apparently nonsensical meaning-making structures of shanzhai writing. We were like, we could think about this forever – everything is in it: questions of property and ownership, access and values, language and hybridity and global cultural exchange and hierarchies and the myths around consumption. So, we’ve been thinking about it ever since.

Who, generally speaking, composes the language on these garments? And how are they composed?

We have our theories about where this language comes from and there’s evidence in the language of many different processes going on – text and imagery directly lifted from a luxury brand design with alterations that appear to be mechanically or personally edited in – and we’ve also had many conversations with people involved in design worlds in Hong Kong and China. But we have not, for instance, had a chance to visit a factory. So, there’s this degree to which it remains mysterious to us what the physical infrastructural conditions are. Of course, the conditions are different from garment to garment. But the methodologies that we’ve talked to people about sound like a kind of chance poetry, a human-machine collaboration that leaves a lot of room for creativity: the translation techniques being used, the various procedures of typing, this one approach described to us of searching on the internet for a particular word and then collaging together the text and imagery that come up. So, let’s say a designer searches for a word – “freedom” was the example given to us – they see what text the internet pulls up, and then think visually in relation to the text to make a composition on the garment. So, there is this blurring of the line between poet and designer, akin to concrete poetry that treats the text as pattern.

It’s interesting to us that this question of authorship is so central to people. It’s usually the first thing we are asked. We have ideas of how the text is made – and you could probably come up with similar ideas – but this question of “who are these people?” is really a question about intentionality. And what’s underneath the question a lot of the time is: but these are really just mistakes, right? You’re over-ascribing intention.

To us, it doesn’t feel that way. We’re not claiming to know what anyone involved in the process was thinking or intending to communicate. We’re trying to describe a phenomenon that the circumstances of global production have made possible, and to read within all of these dynamics the different insights that arise in response to a contemporary experience. So, the question of intention, or the fact that there is so often a question around authorship is, in and of itself, really intriguing to us. If there is any kind of talkback with an audience, the first question is always: who did these? How do you know that’s what they were thinking? Aren’t they just errors? We’re interested in the assumptions behind that question.

I love your point about authorship and the poet-designer. Here, I am thinking about the search engines involved in the process, and then also the nation-state’s own particular regulation of those search engines, how they are involved in the writing as well. It’s really a vast apparatus of inscription we’re talking about here.

That’s what the glitches reveal, right? It’s a diffuse and distributed chain of command that is not so much hierarchical as it is horizontal.

It’s the “meshwork of glitch,” to quote Fan Wu, involved in this chain of command. Based on your interests in the various aspects of multilingual translation and creation of new or non-languages, I wonder how the engagement with the textuality of these garments has impacted your relationship with English? Especially given that one of the trajectories by which this global capitalist enterprise is able to utter is with and through this “English.”

It’s not only English, it’s also French, Italian, Spanish and transliterations from Cyrillic. There’s a lot of pinyin, Romanized Chinese words, as well.

What’s coming to mind in thinking about the appeal of garments that say, for instance, “SAMPLE TEXT” is that a hollowing out of English is also a demonstration of English as the global language of selling stuff. And that the text itself doesn’t matter as much as the demonstration of imperial tongue, of a tongue that signifies power, access, the possibility of luxury, the possibility of riches. “SAMPLE TEXT” is a canonical example of that. It is delightful to see a shirt that so nakedly displays that function.

It’s like a deferral of desire because a garment can state all these aspirational things, “PARIS!” or whatever. But then you get the garment and you’re disappointed. It’s like the potential is never realized. But “SAMPLE TEXT” leaves that open. Insert your desire here. Imagine whatever you want into the form of this, these letters. It’s great.

“The myth of the authentic, the question of real and fake, when you think about it, starts to seem like it’s at the heart of everything that governs our lives. Who determines what’s real and what’s fake?”

This meaning making in the hollowing out of traditional linguistic norms makes me think of Dohra Ahmad’s Rotten English, which speaks to vernacular modes of trying to undo imperial sense or imperial meaning-making at a syntactical level.

That’s the main thing that we’ve experienced in talking to people who make or distribute these garments, an irreverence and casual rejection of caring about English as a meaning-making language. The attitude is pretty much like, I don’t care. I don’t care what it says and I don’t care that it’s wrong. The shirt looks cool and I like the appearance. So, the English is reduced, reduced or elevated, in some way transmuted into image, which is really curious and delightful.

The other day we were talking to some folks who are all doing different kinds of research on shanzhai, and Zairong Xiang offered that he would describe this attitude towards English as one of “radical disinterest.” Radical disinterest as an everyday strategy of resistance. To demonstrate radical disinterest in the correct form of an imperial tongue means that you’re not even giving any energy towards rejecting it, you’re just like: I don’t care. I can’t be bothered.

Shanzhai Lyric is framed as exploring the interwoven state of linguistics and logistics. What drew you toward thinking about them together?

When we were first in residence in Beijing where the project was really born, we were also involved in various distribution practices as art practices. While distributing coffee through the Feral Trade network, we were thinking about how objects move around the world and how to situate art practice within this flow of goods. So, the relationship with logistics was there from the beginning. When we began developing an exhibition framework for looking at and reflecting on and celebrating these garments it was implicit that the inquiry would extend into how they were being circulated.

The Feral Trade project, which was started by the artist Kate Rich, is also a critique of the art world. Coffee and other provisions travel on what she calls the “hot air” of the art world, the excess baggage of the global circuit of curators, artists, art-goers traveling to and fro who have surplus space in their suitcase. By tracing the dispatch routes, Feral Trade ends up becoming a portrait of excess. Similarly, poetry-garments in transit become a tracing or portrait of a certain moment. So, logistics enters into the project on multiple levels. On our website the metadata is part of the story of these shirts. How they circulate is as important as what they say or what they don’t say.

A lot of the research of the past year has been observing global trade flows as they manifest in the space of a single block, Canal Street. Pre-pandemic, we had wanted to follow a single item around the world but, given the circumstances, we couldn’t. When we started occupying a storefront on Canal Street, we realized that we didn’t need to travel because those movements could be studied right outside of our door. Canal Street is a cacophony of languages and cultures where vendors predominantly from East Asia and West Africa peddle bootleg luxury goods to tourists from all over the world. It is a main artery of New York City, and has served as a landing pad for immigrant communities for centuries and is the site of what is considered the first free African-American community in North America. Canal Street was built atop a creek channeled to flow from Collect Pond – once the largest freshwater reservoir for the Lenape peoples and, later, the Dutch colonizers. The original Canal Street industry was oysters and the policing of street vending that began with the oysters has carried down into the discriminatory policies towards African Americans and immigrants that continue today.

The myth of the authentic, the question of real and fake, when you think about it, starts to seem like it’s at the heart of everything that governs our lives. Who determines what’s real and what’s fake? And who are these definitions used to criminalize? The criminalization of the “fake” happens at the level of a bootleg bag, and also happens in how we relate to borders. This is very much on our minds because borders are the ultimate fake thing – arbitrary lines invented to criminalize and contain certain people for the benefit of others. And so the movement of counterfeits across borders is where you can really see the fakeness of the nation in action, and how dedicated the nation is to presenting itself as real through various violent activities.

In more recent times, authenticity also plays a role in the neoliberalization of the city. Canal Street has this lore around as one of the last holdouts of authentic New York grit. But what makes it authentic, which is something that landlords and the government don’t seem to appreciate, is the informal economy of fake goods. It’s the thing that they’re constantly trying to eradicate or sterilize, not recognizing that it’s what gives the neighborhood its desirable “authentic” character. In relation to the street markets, it becomes very visible how the police exist solely to protect the property of landowners. During the pandemic, when the stores here were boarded up, there were no more police because the police had nobody to protect. And so, the street markets really came to life. And as soon as businesses began re-opening, the police returned and were stationed on the block 24/7 because they had people – not even people to protect – because they had people’s property to protect.

Street vendors represent the genuine possibility of upward mobility. If the “American Dream” is a thing that could possibly exist, it exists in the informal economy, because you come to this country and you do not own property and you do not have the means to own property, and so you sell things out of your coat or from a rug on the ground or from a small cart and that’s the way to accumulate capital and to maybe one day own property that you then pass on to your children. That’s the heart of the myth.

This makes me think of Moscot glasses (which is not too far away from you there on Canal Street) and the whole mythos of somebody’s great grandfather, a newly landed immigrant, pushing his cart of eyeglasses around the Lower East Side and, today, look at this giant store with his appearance across it on Delancey Street.

We’re making our way in that direction with the Canal Street Research Association project. Heading West to East, we hope to conclude at Essex Street Market, which is where Mayor LaGuardia basically pushed all of the street vendors into, as a way to regulate the informal economy of the streets and make it less visible. The original Essex Street Market had no windows, because the immigrant vendors are considered a blight on the city, aesthetically unappealing to the modern city.

There is a sentence from Caroline Busta that you quote in your essay in The New Inquiry about “metabolizing the surplus of one’s environment,” how fashion metabolizes the surplus of one’s environment. It makes me think of how you are enacting a kind of counter-metabolism in the Shanzhai project. The thought that rose up with that first one while you were speaking was about the life of Canal Street during this brief interregnum of the streets in the midst of the pandemic and after the George Floyd protests. I’m not sure how exactly these two points connect, but I thought I might offer them up as a kind of partially-connected question-thought.

The way that you phrase this question or offering, connecting that quote “metabolizing the surplus of one’s environment” to acts of theft as rebellion, really prefigures the situation in which we had access to an empty storefront for free. Salient images in the media of the uprisings, like police cars being set on fire, and the so-called looting of luxury goods from luxury stores right here in SoHo, are in some sense what “tore apart the nation” and showed where the divisions in terms of values and perception of reality lie. Because to us, that was an ecstatic moment – to be stealing these extremely valuable and yet utterly worthless items — to be metabolizing the surplus of one’s environment by redistributing the goods.

This is precisely what the Shanzhai philosophy is. Etymologically, the roots “shan” and “zhai” translate to “mountain” “hamlet,” a place on the edge of town where bandits can take the goods from the center of empire and redistribute them on the margins.

We also look to artists who employ strategies like bootlegging and mimicry as a way of reclaiming. There is no definitive history of Canal Street largely because of the illicit nature of the activities that have transpired here or the unofficial status of the people who work here. Therefore, artworks become the street’s main archive. Restaging or bootlegging is a means of telling lesser-known, unofficial, and unsanctioned histories. We think of artists like Elaine Sturtevant, who bootlegs iconic male pop artists’ work such as Oldenburg’s nearby "The Store," to reclaim the narrative.

We also think of different modes of discourse where the commentary is the work. For instance, a Talmudic relationship to text bears some similarity to the relationship that Byung-Chul Han is drawing to Chinese landscape painting, where a central image becomes increasingly surrounded by comments over time. The commentary becomes the work. That feels really resonant with the shanzhai garments where an image is often surrounded by accumulating text and commentary, and that commentary is the work. Then anyone engaging with it can inscribe themselves into it with additional commentary on the commentary.

Credits

- Text: Michael Nardone