Artist SIMON DENNY Is Shaping Berlin’s Disruptive Startup Culture

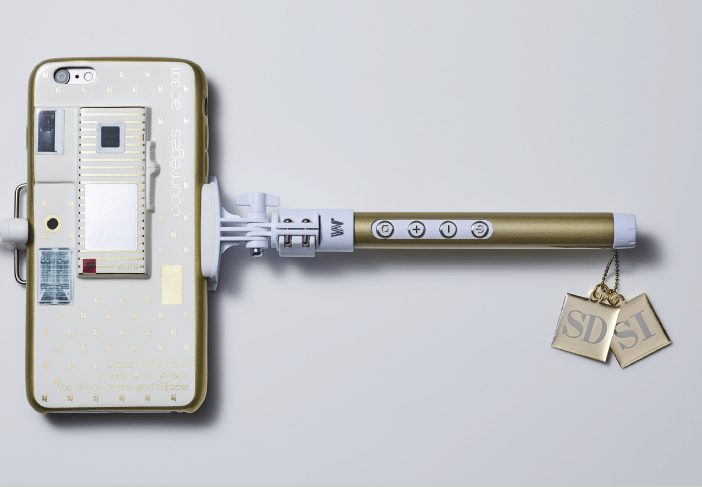

SIMON DENNY opens his exhibition “Disruptive Berlin” tonight at Galerie Buchholz. The exhibition—comprised of new sculptures, videos, canvases, and found objects—is based on the artist’s research on Berlin’s newfound identity as a startup hub within Europe’s tech-based economy. 032c corresponded with Denny about the exhibition and the emergent tech culture in the German capital.

Hello, Simon, tell us about your exhibition “Disruptive Berlin”?

It’s a kind of subjective snapshot of the Berlin tech startup ecosystem in 2013. It’s a complicated thing to attempt an overview of a very dynamic, complex scene—so I have focused on making sculptural portraits of 10 young companies (the top 10 Berlin startups from 2013 according to Wired UK ), and four events—TechCrunch Disrupt, Hy! Berlin, Tech Open Air, and the business accelerator Seedcamp‘s Berlin pitch week.

The title “Disruptive Berlin” uses a term that is commonly applied in this context to game-changing businesses. A great startup will always aim to “disrupt” an existing industry. An obvious example of this is how Apple “disrupted” the mobile phone industry with the iPhone in 2007. That product completely changed an entire market and made all other players at the time totally irrelevant. So “Disruptive Berlin” is a portrait of a highly motivated community intent on changing the way commerce (and life) is done in Berlin and around the world.

The exhibition is an exploration of what this community produces culturally, the values, the rhetoric, the images, and visual content they transmit.

What was it like to collaborate with Seedcamp?

It took quite a while for me to have enough info to decide what to focus on. And Seedcamp’s pitch week was the first thing that stuck out. They are Europe’s best known startup incubator/accelerator, and I wanted to make a video that captured the competitive pitching of companies trying to enter such a program. So I approached Seedcamp and the young companies they were working with and they were extremely generous with access—my film team and I (artist Matt Goetzen, startup video producer Marco Woldt, and filmmaker Johanne Domke) were able to track the entire process of their Berlin Seedcamp week. So their openness was key to producing that part of the show.

I also then had less intense but similar collaborative experiences with more the more straightforward conference-type events mentioned above. Again, all of these events were very open to what I was doing and generous with their material.

Another person that was key to my exhibition making experience was Jenny Jung, COO of Berlin incubator Factory on Brunnenstrasse. She facilitated meetings with many of the people that were key to making the show possible.

Would you invest millions in a company that said they might have the answer, or one that says they definitely have the best answer?

Seedcamp is an accelerator. How does this type of event—focused on pitches and securing funding for startups—differ from tech conferences, which focus more on disseminating content?

It’s much more private event in may ways—more focused and intimate. These young companies have like one shot to show that they are really worth investing in—it’s a high pressure environment. The Seedcamp team are experts in what makes a successful startup, so listening to their tips and coaching was deeply interesting, too. We saw several days of young startup “teams” honing their pitches, and really improving the way they communicated their core ideas and products. Everything was fast and very focused—and this is a real contrast to the more open, social, buzzy, and publicized feeling of the bigger conference events.

How much of this work specifically explores Berlin?

So all of the moments explored in the exhibition have a direct connection to Berlin. They are either Berlin-based/founded companies or events that happened in Berlin. The ecosystem here is rich in young founders, people starting companies, but faces challenges in traditional venture capital—not many big VCs live here. A lot of the funding for startups here ends up coming from larger companies, like Axel Springer AG and Deutsche Telekom, who have a very serious interest in being involved in startup culture. This doesn’t necessarily affect the best startups, like Soundcloud and Research Gate, who have no problem attracting top level investors from Silicon Valley and all over the world. These companies in particular are stand-out, truly disruptive companies—comparable to the best in Silicon Valley or New York.

What promises does Berlin offer global tech culture?

Politically and in the media Berlin’s hyped identity as a startup hub seems to be also culturally very important—maybe even beyond the numbers. Angela Merkel met with the startup community very visibly in mid-2013—showing at least a nominal interest in the sector, perhaps hoping for some of the incredible growth rates successful startups can achieve. Berlin has long been a city in Germany without a truly profitable flagship industry, and above other cities nationally, and even within Europe, it does seem to be a great place to start a company.

In the exhibition I used an infographic that I came across on the English-language Berlin startup blog VentureVillage, which identifies that 44% of startup founders here are not German. It’s indicative of the fact that Berlin is increasingly a draw for young business-minded Europeans. This community is definitely very international and upwardly mobile.

These types of events expand on ways we can participate in society through work. What is their entertainment value?

The entertainment part is quite deliberate—much of the more public events are about promotion at least in part. Hy! Berlin had an almost celebrity-roast format, and borrowed from the language of 1960s chat shows. It felt very entertainment focused. Tech Open Air felt more community focused, and was held at the techno club Katerholzig, so there it felt really more like a festival, a reason to bring a community together in a more casual way. TechCrunch Disrupt was more convention center-like—grand, with high production values and stage settings, dubstep, and distressed, contemporary branding.

But you are right—the way this whole context suggests participation in society can be channeled 100% through work is consistent. Long hours are mandatory, and passion and drive are expected norms. A founder is kind of considered in some of the ways artists often are—to be totally committed and synonymous with the core message and values of their businesses. A founder should be an exceptional figure and have a vision and insight that nobody else can have. They should be able to identify a problem and solve it with tech and business.

These events are saturated in optimism.

Yes of course. Optimism is an important ingredient in any venture, but in tech events the optimism levels are particularly high. In a way this feels like a convention—the saturated optimism levels are systemic. When you see the stats for success or failure in these businesses one also can understand that. The more slim the chances are of success the more optimism might be needed to seem credible. Would you invest millions in a company that said they might have the answer, or one that says they definitely have the best answer? Having said that, all the people I met are also obviously highly intelligent.

Is there room for cynicism?

I think the cynicism might just exist in private, behind closed doors. Its not an attitude to wear on your branded shirt sleeve.

What do you think of entrepreneurship?

I am a fan of the culture of entrepreneurship. An artist is also a business. Many of the principles of work and the world that I see in this community seem very current and relevant. The values associated with entrepreneurship seem very close to me. Highly motivated people with high-risk precarious ideas mixed with efficiency and metrics. What could be more beautiful?