Editorial Roundtable: EMMANUEL BALOGUN and KK OBI, visionaries of Boy.Brother.Friend

This week London publication Boy.Brother.Friend launched the fourth installment of their artist commission series: Mourning for posterity, a video collaboration with Berlin-based performance artist Bonono, whose practice dissolves “the divides between dance, performance and ritual.” The intimate piece makes use of mirrors and layered exposures to reconcile interior experience with external perception – begging questions of endurance and actualization through Bonono’s torqued expressions. Following video commissions from Grace Ndiritu and Alexander Ingham Brooke, Mourning for posterity will be viewable free of charge for 30 days on the BBF website.

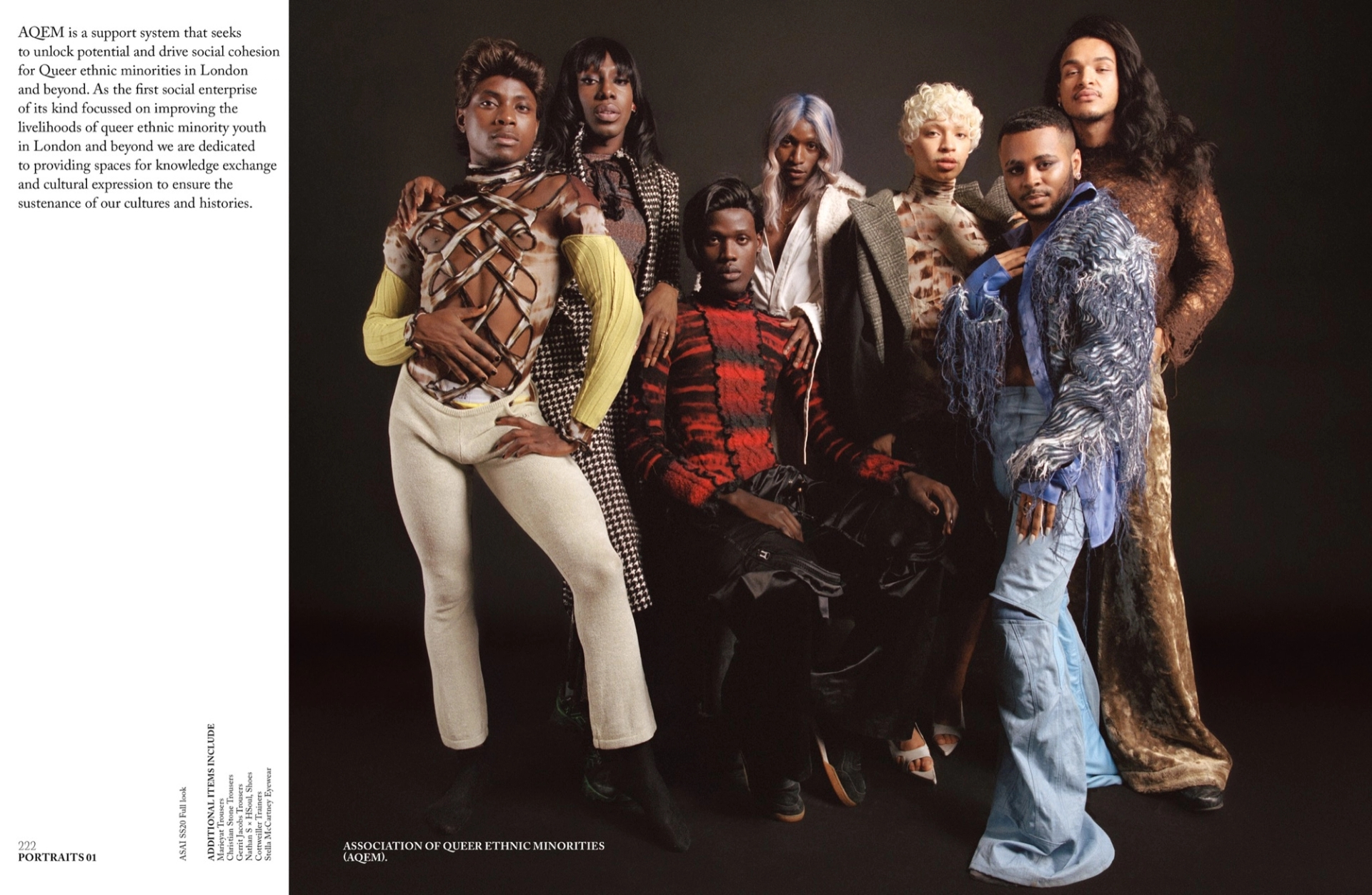

Initially launched as a zine by creative director KK Obi in 2017, Boy.Brother.Friend reappeared in May of this year as a full-scale men’s journal attempting to investigate – or multiply – definitions of “masculinity,” with a specific lens on communities of the African diaspora. “Having skirted different industries in art, fashion, and academia, we felt that we could create something that blends art with fashion while remaining critical – more critical than other platforms have been,” says Emmanuel Balogun, who joined BBF as editorial director as Obi’s vision evolved from DIY project to 250 page print edition and digital platform. “Discipline” is the title and theme for their official Issue 1, which counts Liz Johnson Artur, Damson Idris, Mowalola, rukus! Archive, and the Association of Queer and Ethnic Minorities (AQEM) among its headliners. The publication hopes to expand its geographic remit as it evolves, but the heavy presence of London creatives in this first iteration was by design. Keeping it close to home, the debut is survey of friends and collaborators, often “people who occupy positions that aren’t usually at the forefront visually” – curators, casting directors, advocates, and others who are “part of the ecosystem.” Collaborating with creative producer Priscilla Yeboah-Newton, art director Jules Banide, and digital designer Dan Adeyemi, Obi and Balogun wanted to create “a publication that starts with masculinity, but it can’t be understood through men alone.” 032c loves new independent publications – especially when they fill an industry void, and when executive editor Victoria Camblin and assistant editor Octavia Bürgel spoke to Obi and Balogun, they went full magazine nerd.

Octavia Bürgel You launched Boy.Brother.Friend midway through an already eventful year, how was your initial reception impacted by the events of this spring?

Emmanuel Balogun: The timing is interesting because there’s two ways to look at it. When we actually launched, on May 8, it happened to be just before George Floyd was murdered, and the response that we received in the beginning increased after we saw our whole community speaking out about social injustice. More people were ready to hear what we were saying, outside of the people that we had already sent the press release. So that’s a question: why were people more willing to respond when the press release we wrote initially ratified a lot of the things that were already being said? Intersectionality, race, social injustice – these are conversations that we know as people with hybridized identities. KK was working on publications like (African global style and culture magazine) Arise over 10 years ago, and we were fighting, advocating for the Continent way before people would even listen outside of Africa. Why do people have more of an interest in the Continent now, when Africa has been rising for decades? It’s only now that there’s a business case for actors to be involved.

We naturally have a diligent nature because there have been so many qualifications of Africa, emerging markets, and ethnic minorities. Being those things ourselves, we felt we had the tools to represent our friends, our communities, and ourselves truthfully – with the elegance that we feel they deserve. Other platforms have tried to document certain people, and I think you can always tell how close they really are to the subject.

Victoria Camblin: This idea of truthfulness connects to the difference between surface representation and representation in actual media production – the difference between who is on the cover, and who is running the magazine. Would you say that what people respond to is authenticity?

Emmanuel Balogun: I think it’s about due diligence and curiosity. How curious are the editors? How curious are the producers? How curious is anybody that wants to work with anyone? What sorts of questions are they asking? What are they really thinking about? When you start asking more questions, you start understanding intentions, and that helps. But to be honest, I think authenticity is very loose. The kind of considerations that go into a wide audience facing platform versus a niche one – they’re different. I write and contribute for different titles, and certain arguments are relevant for their readers. Some arguments won’t even be decipherable to certain people’s readers, so it’s quite gray.

KK Obi: To add to that, I think people can smell bullshit. What’s the point of having a conversation if you’re not going to have the real conversation? I know that there are certain institutions or brands who obviously are more audience facing, but I feel like we’re in a time where we all need to be clear and direct about what we’re doing, and if people are attracted to that message, then they are. These are the lives we’ve lived, and it felt like there wasn’t anything that represented our history, especially within the fashion world.

Emmanuel Balogun: The industry, or industries, need to be democratized from all positions, so that when you have a group discussion, you get a real diverse picture. Why did everyone working in certain positions all go to the same school? Why do they all live in the same postcode? Why do they all have the same family net worth? If you look at most mastheads in magazines or galleries or wherever, there’s no diversity from a class element. And that, for me, is why things get muddled up, and why we don’t even know what authenticity is. Authenticity is also a sliding scale: everybody is being authentic to who they are based upon where they came from. So until we democratize things, it’s just going to look the same.

“Why do people have more of an interest in the Continent now, when Africa has been rising for decades? It’s only now that there’s a business case for actors to be involved.”

Fashion and art are weird because they are such fast industries. The zeitgeist moves so quickly. But when it comes to diversity, when it comes to sustainability, they’re lagging. Corporate sectors have been talking about advocating things like social governance, ESG, for a long time – long before fashion started talking about it. The tricky question is: Do people care? We are in a moment of change. We’re starting to question what growth, what “more” actually is. It’s now becoming understandable why so few beneficial services are profitable. And it’s clear that this time of Covid has made people way more conscientious.

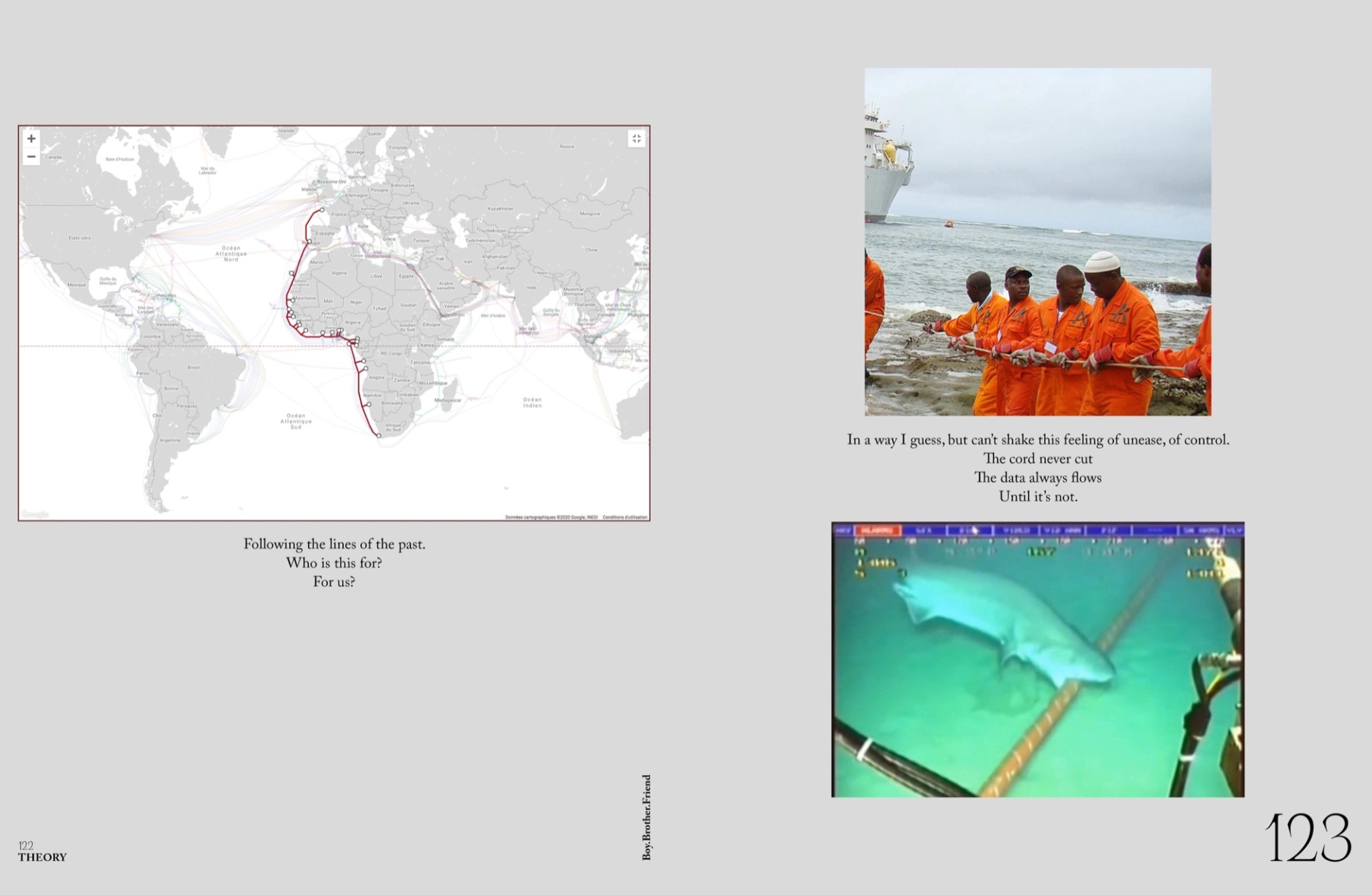

Victoria Camblin: It lifted the veil, right? Revealed how goods and images and information really circulate. Maybe there is desire for some kind of inherent acknowledgement of transparency of the process.

KK Obi: The process is important – as a stylist, it’s really, really hard to have conversations at the moment about clothes. I used to talk about old shows or moments in fashion that I liked with friends of mine. People don’t really want to talk about that anymore. I think to connect with people, you have to be, as you said, more transparent and more honest about the processes, the origins, the reasons, the detail behind a given product. More than ever, people want a story that’s real. Also, everyone’s suspicious now. They think everything is fake. You have to make the extra effort to really try, even if what you’re saying is real. We live in a time where every day is noisy, and it’s hard to cut through that.

Octavia Bürgel: Boy.Brother.Friend is successful in that it feels like the community within those pages is the same community that you are immediately surrounded by. How does that relate to this idea of authenticity, or on the other hand of diligence or curiosity?

KK Obi: We wanted this first issue to have a very solid London focus. I didn’t want to be trying to reach someone in a different country where I haven’t spent time. I know London, I think, relatively well now. And luckily, we’ve met some amazing people who are talented in many, varied ways. That’s what we wanted to focus on, and I hope that’s what the pages show. Because we know these people, we know what they are willing to do, and what they don’t want to do. That knowledge also shows that we really care about their creativity, their processes and their lives.

Emmanuel Balogun: You have lots of different portraits in there, and some are more daring in terms of the styling options in ways that I’d say fit those people’s personalities. You’ll notice there’s a quote that aligns with each person that’s shot in a portrait series, talking about how their practice supports them in advocating for change, or how it supports them in terms of self-actualization. It is a very personal process of speaking with people and, obviously, also checking that they were happy with the final words that were featured. We didn’t want anything to run in a way that people weren’t happy with. Not everybody was someone we had known for 10 years – there are people in there whose work we respected from afar, and who we got to know through the process. It comes down to the questions we ask, to the way that we approach people. It’s that element of care which funnels down. Because, obviously, it’s a publication, but we’re a community.

Victoria Camblin: This idea of mutual care is implied in the relational title, Boy.Brother.Friend. The stages of man. To the diaspora focus you add of course the theme of masculinity – how have you approached that topic, in light of the adversarial and “toxic” versions that have dominated in media in the last years?

Emmanuel Balogun: There are affirmations, bell hooks and Cornel West quotes, interspersed throughout the issue – that’s one of the ways. Those quotes come from a book called Breaking Bread. I suggest anyone read it. It looks at the relationships between Black men and Black women historically and the work that they have to do in order to love each other as siblings or even in conjugal roles. We do look at masculinity in the sense of what is it like to be a man? And what is it like to be with a man? There’s an op-ed type piece in this issue called “This Is a Rant” by Shakeena Johnson, who’s a fab writer who says what she feels. She’s a beautiful Black woman from London, and she wrote about her experience of a love that didn’t work out the way she wanted it to. If you read it, you’ll really understand why the magazine needed to be a response, a conversation between more actors than just cis men. Some people found it quite a contentious piece for the things that she said, but I think a lot of Black women in the UK and beyond can side with her and say that they have felt that way with Black men at times.

Octavia Bürgel: I thought Shakeena Johnson’s piece was great. I could see how an audience that might have been expecting the scope of BBF to be more traditionally patriarchal might have found it controversial, but as a Black woman, to come across that as one of the first texts in the magazine was an indicator of the project’s intersectional approach, which I really appreciated.

KK Obi: I feel like masculinity has meant so many different things to me, growing up in Africa, and now being in London. At times feeling like I wasn’t masculine, or that I was being too masculine. I think the definition changes in everyone’s perspective, really – but society maintains there is some weird code that we’re all supposed to adhere to. I always wanted to investigate that, to really figure out what those rules are. Because in some ways, I couldn’t really do that in my own life, so I felt like my work should try to represent it in some way. Masculinity in the diaspora means very, very different things as well. I wanted to try to unpack all of that in one space.

Emmanuel Balogun: The post-colonial experience is really interesting in terms of masculinity and its formation. Thinking about what I’ve learned from my father’s generation – people who potentially lost power, or were born into not having power, or into sort of a servitude, racially – how did they define themselves as men when they were unable to be who they wanted to be, unable to occupy those preset roles in society from maybe a work perspective or financial perspective? How could they provide? “Providing” – what does that even mean? In terms of the Continent? And what about being uprooted from the Continent? If you move from Africa or any emerging place and go to the West, you’re trying to create your own understanding of masculinity based upon a lot of social factors. I think we have a lot to unpack about masculinity and the forces that can disrupt the construction of a personal definition of it, not to mention the way that other people see you. That’s the landscape we’re thinking about – not just from a post-colonial standpoint, but in terms of how we even think beyond that, in the sense of liberation. There are so many things to be said about masculinity, especially now that we’re finally starting to practice understanding different denominations of gender.

Octavia Bürgel: Angela Davis has written about the convergence, the shared temporal relationship, of anti-slavery abolition movements, suffrage for the Black (male) vote, and women’s suffrage in the States. Ultimately, this debate over who would be seen as human in the eye of the law pitted Black men and white women against each other, erasing Black women from the narrative entirely, because they weren’t seen as belonging to either group – neither man, nor woman. The way in which the standard of “femininity” was created in the image of white womanhood is something that Black women and anyone operating outside of the binary feel oppressed by regularly.

“I think the definition of masculinity changes in everyone’s perspective, really – but society maintains there is some weird code that we’re all supposed to adhere to. Masculinity in the diaspora means very, very different things as well.”

Emmanuel Balogun: Labels are useful to think with, but they’re also so hindering when we start attempting to classify ourselves. We do that for many different reasons and purposes and effects, but sometimes, they’re just pointless. I think Mark Sealy says we get tied up in “epidermal schemas.” We’re trying to really unpack and dissect that to move forward as a community. That’s why we had Damson Idris on the cover with the handheld mirror, looking at himself. We have to criticize ourselves constantly for productive ends, as a community – whatever your creed, age, color, gender. It’s for us to move forward collectively.

KK Obi: That’s the key: we have to be critical of ourselves. We have to say, “Okay, we’re not perfect. What else is going on? What conversations can lead from that place?” For us to evolve, criticism is key.

Octavia Bürgel: The reflexivity of the critical attention that you mention is leaving space for fluidity, which is a notion that gets referenced a lot in relation to the ontology of Blackness.

Emmanuel Balogun: People need to move. It’s human nature to move. There’s an anthropologist, Liisa H. Malkki who said “To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul.” It’s a beautiful line. Humans have to move, but we also have to be grounded somewhere.

Victoria Camblin: Is there something specific to the format of a magazine or a zine, in terms of a production model, that supports a particularly fluid or intersectional approach? A periodical, as opposed to a one-time publication, allows you to commit and return to and evolve certain conversations.

Octavia Bürgel: The magazine also functions as its own archive, contained within each iteration, then becoming part of a larger record. I’m reflecting on the notion of a Black archive, which has always existed in fragments. I think that is why many young Black artists for example are working with archival materials now – attempting to process the de-historicization so many of us have experienced, and trying to stake some claim to the world going forward. It’s quite a potent space that you’re realizing.

KK Obi: My education has been in print, dating back to when I was at Arise. The frequency of a biannual is something that works for us because, as Emmanuel said, we have limited resources. As we evolve, who knows how that’s going to change. But having something that’s physical, that is essentially a document of a time, of a community, is very important to what we’re trying to do.

Emmanuel Balogun: It’s essential that we produce this work for the people that will come and for the people that are here now. It’s important for people to see themselves in physical items, in publishing efforts that are of good standard, so that they can feel ratified, I think. So that they feel their existence is valid. Hopefully the magazine will sit in libraries for years to come. There are publications that I’ve been looking at for years that you just can’t find sometimes. I’m sure you can relate.