Silence = Death: Remembering New York’s Public Art of AIDS Activism

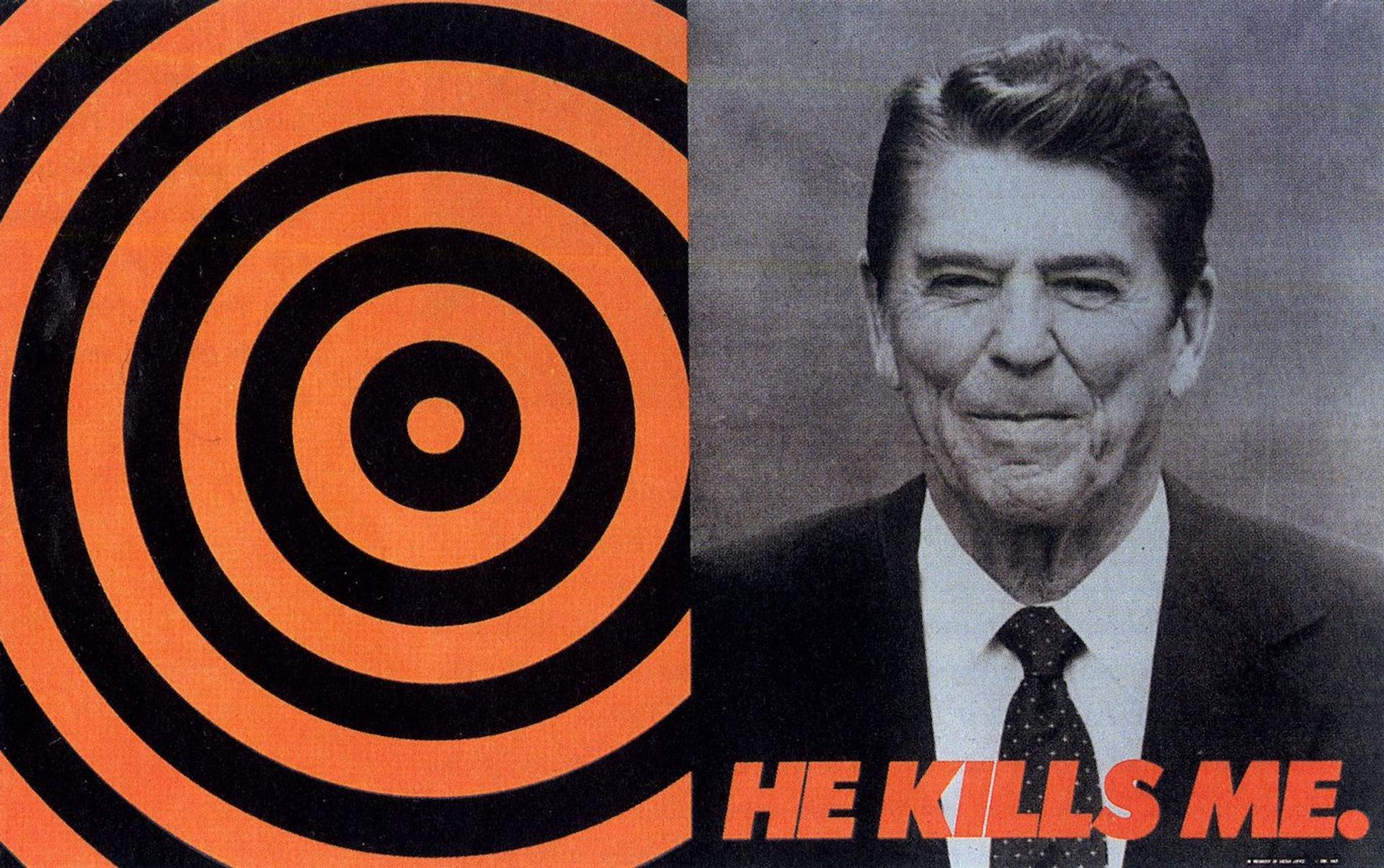

At a time when the AIDS epidemic was surrounded by injustice and confusion, collectives such as Gran Fury and Group Material mobilized themselves not simply as artists, but as activists in a larger political arena. Often appropriating the visual language of advertising, they disseminated messages geared towards a public that was largely misinformed and suspicious towards their cause. For his upcoming book, REBELS REBEL: AIDS, Art and Activism in New York, 1979-1989, Tommaso Speretta has compiled a collection of essays and images from the frontlines of AIDS activism.

What motivated you to take on this project?

TOMMASO SPERETTA: This research project has been on my mind since college. While I was a student, I attended a lot of classes that dealt with the idea of public art – somewhat influenced by Nicholas Bourriaud’s idea of relational art at the end of the 1990s. I wasn’t totally convinced by the idea that, for instance, installing a sculpture in a public space was a sufficient condition to define that work as public. After graduation, I started researching examples of public art, which really addressed the need of involving a wider audience outside the strict circles of connoisseurship. This is how I came across AIDS activist art – widely represented by the art collective Gran Fury that was working with ACT UP – and activist art movements which arose before them in the 1970s. I think these movements were perfect examples of how art can be really interfere with public opinion and contribute to social change.

Was it difficult to unearth these materials?

At the time, many collectives were more concerned with their goals rather than at properly archiving and documenting their work, so it was sometimes really hard to find the correct information and materials. In any case, much of the material was recovered with the help of the artists involved. They provided me with images, press releases, original material, and their own personal stories and memories. In addition to this, the help of art historian Douglas Crimp was essential in guiding me through my research. The New York Public Library was also an important instrument for my research – the entire Gran Fury and ACT UP history is preserved in there. That said, museums are now slowly introducing these artworks in their collections, even though they usually stop at the most obvious artworks – like Silence=Death’s pink triangle and such. It would be great to see other artworks included in major museum collections.

You describe the artists in this book as practitioners who operated on the fringes of the art world, sometimes even outside of that realm altogether. Do you think the direct political engagement achieved by collectives such as Gran Fury and Group Material is possible from inside the institution?

Yes, I think so. I try to make this clear in my book, often using the artists’ own words. Two important examples are: Democracy realized by Group Material for the Dia Art Foundation in New York in 1988 and The Pope and the Penis realized by Gran Fury for the 1990 Venice Art Biennale. Both collectives had big doubts and long discussions before accepting the invitation of two big institutions like Dia and the Venice Biennale. Group Material decided to take advantage of Dia to talk about the state of crisis in which US democracy currently was trapped. Gran Fury showed explicit images to criticize the position of the Catholic Church and get worldwide press attention. They weren’t at all naïve. They used precise media strategies to achieve this, and using shock value was just part of their deliberate tactics.

The artists involved in AIDS movement of the 1980s responded quickly and loudly to a government that seemed callously indifferent to the death of its citizens. Are there political circumstances today that you believe can mobilize and unite artists in such a way?

I live in Italy, and if we consider topics like gay marriage, homophobia, or sexual discrimination in the workplace, for instance, then there would be a lot of issues that should convince not only artists, but a wider public, to unite together and shake the public opinion. I am often quite terrified when I read the comments readers leave on articles published in the biggest Italian newspapers which deal with representation of homosexuals today. The same could be said for the constant and continuous political instability we’re living in. And yet, we still seem anesthetized to these issues. Group Material’s main aim was to engage the largest audience possible with cultural activism. And this might still be a valid strategy today. What I wanted to do with my book was offer examples of how artists and the art world faced a period of political crisis. Activism mainly means organizing a community, and this community organizing can come from the art world. When ACT UP formed in March 1987, it was also helped by an artwork that appeared in the streets of downtown Manhattan – the famous Silence = Death poster. I think we can learn a lot from history. We now need to understand how to translate this past into a future.

Rebels Rebel: AIDS, Art and Activism in New York, 1979–1989 is published by MER. Paper Kunsthalle (Ghent, 2014).