Salty, Litigious, Iconoclastic: DAVID SIMON on TV as discourse

This Friday, January 11, marks 20 years since the first episode of The Sopranos aired on HBO, inaugurating what would soon be referred to as “The Golden Age of Television”: auteur-driven, long-form programming of which The Wire was an integral cornerstone. As the blueprint continues to unfurl into an array of streamable dystopias and mega-budget content smoothies, we revisit our 2011 interview with The Wire creator, writer, and show runner David Simon, whose most recent series The Deuce was recently commissioned for its third and final season.

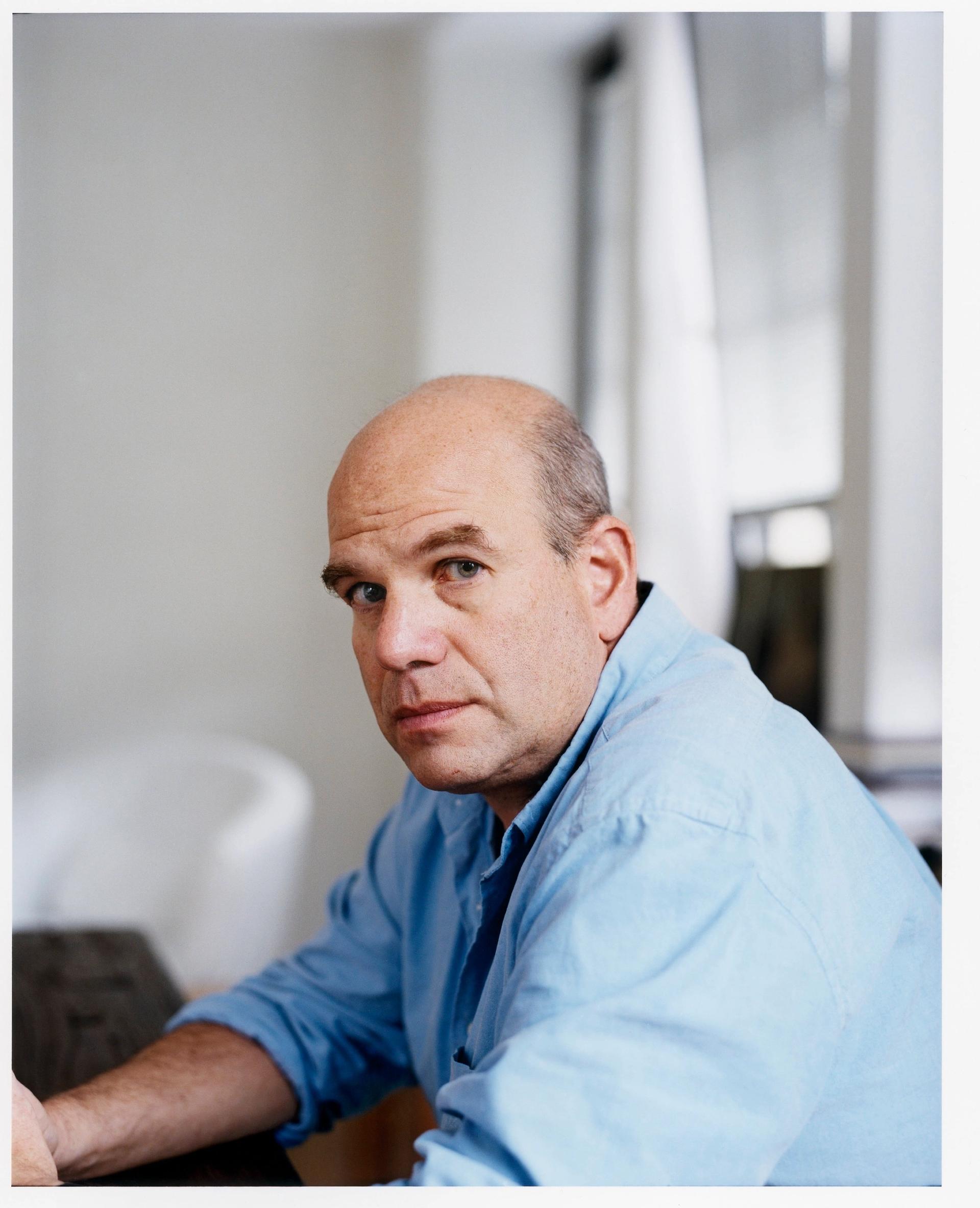

DAVID SIMON (b. 1960) accomplished the unlikely feat of captivating both West Baltimore bruisers and New Yorker subscribers for an hour a week, over the course of six years. Simon created, wrote, and produced The Wire, which aired on HBO from 2002–08, and whose acclaim has garnered the former police reporter a reputation uncommon among even the most lauded of screenwriters. What starts out feeling like a cop show (and not a particularly stirring one) along the lines of Simon’s previous small-screen gig, NYPD Blue, pans out into a captivating social realist panorama of metropolitan Baltimore, an experiment in unhurried storytelling narrated through the interwoven lives and deaths of the city’s most powerful and most inured citizens. Television, according to Simon, is a platform for discourse.

Simon has the comportment of someone who works with his hands. He speaks in full sentences, effortlessly switching between the soft tones of a salesman, and the salt of the earth candor of a rust-belt union leader. Two years ago, he was the subject of an exposé by Mark Bowden for The Atlantic, in which he was maligned as a man compromised by his personal grudges. The piece might be hyperbole, but its title – “The Angriest Man in Television” – stuck. Perhaps it touches on some grain of truth: Simon has many complaints and no qualms about expressing them, both in his scriptwriting and in conversation, such as the one we had with him in Cologne some days before he received the TV Spielfilm Award there. From season to season, The Wire proceeds like a check-list of the social woes he began to scorn when he took up his post at The Baltimore Sun in the early 1980s: drug wars, post-industrial dereliction, crony politics, the failure of the education system, and the decline of the American newsroom.

Though he would claim to the contrary, Simon writes with the intent to instill a certain, left-leaning, social consciousness in his audience. “We’re not just grateful to have a job, enjoy the craft, and get paid for it,” once explained Sonja Sohn, who played The Wire’s Detective Shakima Greggs, “We think we’re doing something for society.” Aside from critics who have variously described The Wire as “the best TV show ever to broadcast in America” (Jacob Weisberg, Slate) or deserving of a Nobel Prize in literature (Joe Klein, The Washington Post), many of the show’s endorsements have come from those who see its potential for social impact. Barack Obama famously named it his favorite show, and last summer, Jón Gnarr, the new mayor of Reykjavík, made watching all five seasons in their entirety a prerequisite for party coalescence.

The night before meeting Simon, we attended a screening of the pilot episode of his latest series Treme, centered on life in New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. Faubourg Tremé is the part of the city that gave rise to Jazz music in the 19th century, a place where African rhythms freely mixed and integrated with European musical traditions. For Simon, it’s the veritable birthplace of what he considers America’s single most important legacy, and as the representation of a possible American cultural renewal. Dominating the pilot episode are the blazing brass bands that Simon sent into the still-ravaged neighborhoods to exorcise the city’s collective tragedy – if not The Wire’s perceived pessimism.

Many call The Wire “influential,” but if Nielsen ratings are any kind of barometer for influence, then it is not: The Wire’s languish far below those of The Sopranos. His viewers are few, but they are fervent. The extent to which Simon’s long, challenging narrative arcs – in which cause and effect can take several seasons to resolve – and inscrutable verisimilitude will encourage richer forms of storytelling amidst today’s twittering buzz of fast information remains to be seen. What is certain, however, is that the question of mass acceptance is unlikely to dull Simon’s taste for contemporary sermon: his concern, as he has repeatedly stated, has never been with mainstream success, but rather with the perhaps even more elusive possibility that those represented recognize themselves in the work. As his series travel from one conflict zone to the next – from West Baltimore, to Baghdad with Generation Kill (2008), and most recently to the ruins of New Orleans – Simon won’t be running out of material any time soon.

You know, John Waters’ work is being featured in this issue as well.

Oh, my buddy!

Have you guys worked together?

We’re both from Baltimore, and we share the same crew base in the city – right down to the grips and gaffer. Vince Peranio did all of the art direction for his films, going back to the early ones; he was also was the art director for Homicide, The Corner, and The Wire. Pat Moran was the casting director for all his films and for The Wire. After a few years, I got to be friendly with him.

You wrote in a joke about Waters in the Season five – something about him and child actors?

We ran that by him. It was a joke, sort of at his expense, but he liked it. We wouldn’t have done it without him enjoying it – it was our little tip of the cap to John Waters. He is, by the way, a genuinely brilliant writer. Laura [Lippmann], my wife, turned me onto his books, his essays and his reflections on society, and he’s really sharp, a very bright man. I didn’t become a fan of the films very early on, not like Polyester early, but I found my way to them and enjoyed them for what they are. Over time they became real Baltimore touchstones. They’re almost all filmed there, though he may have to go outside Baltimore for the next one because of the incentives in other states – the “get-backs.”

You have mentioned before that you saw that each season of The Wire as another step in the process of rebuilding another slice of the city: the docklands, the school system, the local paper, the city hall. It’s interesting to think of a city being re-built through a TV series – in the sense, for example, of Italo Calvino’s Invisible City, where each chapter of the book describes Venice in a different way.

I don’t know if I ever meant “build” in a physical sense. But I think many authors have done that, with many different cities. I am not making a comparison of the relative merits of The Wire to great works of literature but you can look at Balzac’s Paris, Tolstoy and his Moscow and St. Petersburg, or Armistead Maupin’s San Francisco. I mean, using a city as a backdrop to explore society as a whole over time has been a leitmotif in literature.

The idea of building and changing a place through narrative is what struck me as interesting. Doesn’t storytelling have the potential to effect some kind of social change?

I gave up on it when I was still in journalism. When journalists start to believe that their stuff is going to change the world for the better, they start to cheat – they start to distort the story. It starts to become a means for winning Pulitzers, and so they add something that they think will demonstrate the impact of their journalism. The storytelling that was honest, direct and fundamental becomes secondary to this fraud of impact-journalism. I saw that happen at my newspaper, The Baltimore Sun, and I hold it in the greatest contempt. Somewhere in the middle of my journalism career I stopped believing that journalism could be a positive force in the world.

Would you also say that about the investigative journalists covering the escalating Mexican drug wars?

What, because journalists are being killed? I think it’s important to tell the truth and I think these journalists are risking their lives to tell the truth. But going out there thinking it is going to get better because of their journalism should not be necessary. The act of bringing a story back to the campfire, one that is the closest approximation of “true” that can be achieved, alone is the elemental and most worthy goal of journalism. Look behind any newspaper crusade and you’ll see the self-aggrandizement and the self-absorption of a couple of newspaper people who are no longer interested in merely telling an honest story.

Is it a question of authorship? It took me a while to understand The Economist’s practice of leaving some pretty great stories unauthored. It’s the story that speaks, not the who.

Now, I think bylines are important. Not because they give credibility and cachet to the people that have them, but because it makes people responsible for what they wrote. You can’t hide behind anonymity. I understand your impulse, but I see it the other way. I saw a lot of bullshit at my paper, and it never failed to impair the actual journalism. Complicated stories that had more than one side suddenly became simple; stuff was over-reported. People went for anecdotal leads that were hyperbolic, that really weren’t justified by the story and then eventually, people started making stuff up. What I most admired about journalism was the simplicity of the act: “It’s my beat, and I know all about it, but I just learned something else so I’m gonna go and find out more. And then, like the village crier, I’m gonna tell you and you’ll know. It’s a good story, so you’re gonna want to hear the end of it. And then I’ll go back out to do it again.” Now, if as a result of that, enough stories convince somebody to do the right thing policy-wise, then great, but that’s not my job.

Storytelling happens very differently in your new show, Treme, than it did in The Wire. You said at the Cologne Conference (2010) that New Orleans is more desolate than Baltimore ever was, that the public schools there make those in Baltimore look like the Ivy League. So if New Orleans is even more dire, why doesn’t Treme employ an amplified version of the Greek tragedy realism of The Wire? Why make it affirmative storytelling, as you say?

I think that there are some affirmative moments, but I don’t think it’s going to cheat the fact that New Orleans is dystopic. I won’t represent New Orleans as something other than what it really is, but I’m also not going make another story about what public education is up against. I just did that. Life is short, and I don’t want to make the same film twice.

With The Wire, I felt that you short-changed the cultural aspect of the ghetto. While Treme is all about Jazz music and African-American culture, The Wire did not show the drug dealers’ cultural lives. One of the only times they talked about music, for example, is when Marlo’s assassins, Chris and Snoop, interrogate out-of-town dealers with local rap trivia. It was that radio show, that music, that brought all the different factions together – why not celebrate that?

Well, when Cutty comes home in Season three, we showed them having a party with blasting Baltimore club music. But The Wire universe wasn’t set up for it, and that wasn’t the purpose of the show. Culture was an aspect of America that neither I nor the other writers could get to. With Treme, the idea is to see the city as not primarily political, social or economic, but in a way in which it’s the seed for something that matters to the American psyche. Yeah, there would’ve been a possibility of celebrating culture in The Wire, but we didn’t do it; we saved it for Treme. I don’t know if you know what Bounce music is, but it’s New Orleans’ hip hop and we’re putting a lot of it in the second season of Treme. Also Sissy Bounce, which is its own variation, transvestite bounce music. Now, we’re doing the cultural aspects of the American city, and a very unique American city, one predicated on culture.

Since the beginning of television, Americans have understood what they saw on TV as a kind of ideal. Shows like Leave It To Beaver, The Brady Bunch or The Cosby Show have provided models of the nuclear family. By and large, television has tried to provide an idealized mirror for its viewers, but your shows don’t. In fact they show the dirty reality, with all its profanities. What dynamic do you want to strike with your audience?

The Wire never professed to be the story of the most viable, functional and economically secure parts of America. It’s a show about the other America, the postindustrial part that got left behind. There are more broken families, more drugs, and fewer jobs – that’s the other America. It’s the America that has gone under the waves of change instead of riding them. And the country is more and more schizophrenic as a result. All those sitcoms of happy funny families and all the warm stories of cops solving the cases, that is a viable America that may in fact reflect certain realities of the country, but surely not all the realities. The Wire never claimed to be universal; any story that tries to tell the story of everything tells the story of nothing. The goal was not to say, “Oh, here’s a drug dealer,” but to ask, “Why is he a drug dealer, where did he come from?” And whenever somebody says, “The Wire doesn’t show all the great jobs in Baltimore’s computer industry; it never went to the Johns Hopkins campus,” I’m thinking, “You’re a fucking idiot if that’s really the way you evaluate narrative.” Because what they’re saying is that The Wire’s too negative. What they’re saying is that the television universe offering one show that addresses what we’ve done to our inner cities, to our minority population, and those that are in the industrial working-class, is one show too many.

If there are two Americas, does that mean we need at least two different ways to address them? Where your shows seek to convey reality, Jon Stewart’s Daily Show parodies it. But what you share is dissatisfaction with the mainstream’s representation of America.

Jon Stewart gets closer to reality than the news. It’s brilliant writing.

Exactly, and people have started to rely upon it as their main source of news. Time magazine polled more than 9,000 Americans online, and it turns out that Jon Stewart is America’s most trusted newscaster.

I think people know that they’re watching parody. What’s telling about Jon Stewart is how sane his satire and his stance are compared to the political and journalistic infrastructure that he’s goofing on. American politics have always been liable to satire. But 24-hour cable channels today are an abomination. I say that not just about Fox – you know my politics are quite to the left – but also about MSNBC. On both sides the ideologues are having their way. Ideology is the great motivator in television news at this point, but ideology is worthless. It’s remarkable how susceptible the networks are to Jon Stewart’s savagery, to his wit. He must get up every morning and read the paper and think, “It’s too easy. These guys are just idiots.” The stuff that comes out of their mouths is shocking.

It’s like Tina Fey doing Sarah Palin – you just have to read it verbatim. But what does this say about the power of parody? In the end, is The Wire’s verisimilitude simply perceived as entertainment?

Right, but I know what I’m doing, which is making a drama, and there’s cheating involved. I’m not cheating to the point where I’m saying something dramatic that isn’t true. That would violate my purposes for doing it. What I’m doing is not journalism, but what I do is rooted in its ethos – and that’s an important distinction. I get to stack the deck, but I’m not stacking it so much that I’m ignoring counter-arguments against my views. I also show you that inside that zone, there’s a human apocalypse. When people ask me if any of these scenarios actually happened, I always say that some of it happened, some of it was rumored to have happened, and some of it never happened, but it could’ve.

You’ve also said that many of your characters are based on real people or at least combinations of them. Is there one that is 30 per cent David Simon?

No, but people read me into McNulty.

What about Gus, the honest, fact-checking metro editor from the fifth season, who tried to uncover the fabrications of a prize-hungry reporter?

No, I was never an editor. But there were two or three editors that I really admired when I was at The Baltimore Sun. There is a little bit of Bill Zorsi in Gus – he was a desk editor – but especially Rebecca Corbett and Steve Luxenberg. Luxenberg is now on contract at The Washington Post, and Corbett’s an editor at The New York Times. They are the people who helped train me and made me a better reporter. But to the extent that anybody could say that I’m embodied by a character, it would be the black reporter, Fletcher, who ends up pulling a story out of his encounter with Bubbles, the recovering drug addict. By random chance, Fletcher meets the guy, the guy appeals to him and he writes an honest story. He wasn’t me either but at least he was representing the best that I can say about my work at the Sun. When my stuff was good it was organic in the same way Fletcher’s story is and I was definitely reliving something there. I’m infinitely amused to find out what people credit to me and what they don’t credit to the actors or to the rest of the writing room. It’s not one guy with a typewriter. In the first part of Treme, for instance, there is a scene where John Goodman’s character is ranting, and American reviewers heard my voice in that: “The angriest man in television,” they wrote, “that’s him.” But the rant is actually taken, in part, from a blog by Ashley Morris, which you can still find on the Internet. I didn’t even write the scene, Eric Overmeyer did. But literary criticism, which is always a dubious prospect, now strains everything it sees through what they know about David Simon.

“The Angriest Man in Television” was the title of the Mark Bowden piece that appeared in The Atlantic.

Yes. Mark was close to a couple of the editors at the Sun whom I held in low regard. Even before season five, which was largely set in the Sun’s newsroom, he was clearly worried that I was about to make their lives less pleasant. Mark fired a shot in advance with that Atlantic piece because I had spoken very openly about what I regarded as bad behavior on their part at the Sun. Mark’s article was as dishonest a piece of journalism as I’ve ever encountered. At one point, he wrote about how I went off on his friends at the “Stoop-Session,” an event I did for charity. A number of us were asked to speak for eight minutes on “My Nemesis,” a theme the organizers had selected. Of the eight people that spoke, six chose to speak about ex-bosses. But Mark carefully didn’t say all this. What he also left out is that at the end I made a joke about how I failed at having my great revenge and everybody cracked up. But now you go to Wikipedia and “revenge” will be under my “motivations for writing.” Apart from that, being the angriest man in television makes it a great thing to go into a room in LA. It’s like, “don’t fuck with him, he’s the angriest guy around.”

You obviously hold journalism, or writing at least, in high regard. You mentioned literary critics analyzing your work through your personality, but it seems that The Wire itself offers a high level of linguistic complexity for them to chew on: the authentic use of “Balmerese,” Ebonics …

We worked hard on that. These are writers who love language.

Apparently even some of the native Baltimore actors were not allowed to improvise, because you and Ed Burns, your co-writer for The Wire, had understood the Balmer accent better than the actors?

The actors had a hard time with it. The white Balmer accent is like, “Yuh tawk like thish and I’m not ign’rant but I tawk like thish.” It’s from the south of England, supposedly, and it resulted from being isolated around the Chesapeake Bay in the 1700s. It’s really unusual.

You play out your fascination with language in the script. Did you write the scene, which was at some point in season one where McNulty and Bunk’s entire dialogue consisted of the word “fuck”?

The initial idea came from Terence McLarney, a detective sergeant in the Baltimore homicide department, who’s a good friend. He said, “in the unit, we are so profane that eventually we’re gonna get to the point where we’re only gonna use the word ‘fuck’ to communicate with each other. You’ll see two cops standing over a crime scene and just saying ‘fuck’ back and forth and still get their job done.” We all laughed. I remembered that and I brought it to Ed Burns, who had an incredible amount of fun with it. He wrote the two-page scene that we brought into the set. And when we got to film, in order to fill it up, we brought the actors into the loop with additional lines of dialogue: “Fuck, fuck, fuckity, fuck fuck.”

So, television can even be a platform for interesting linguistic discourse – it makes people think.

It can be a platform for anything. And considering how prevalent and pervasive it is in our society, it’s been a platform for remarkably little other than selling shit. That has been the history of television for 50 or 60 years. We sell shit, and then we put some programming around that to keep you watching. But you get rid of the advertisers, and people start thinking a whole another way.

If newspapers, your previous medium, “went bad” in the mid-Nineties, what do you think of the current state of your new outlet, television? Do you watch any other TV shows?

I don’t watch a lot of TV, and I never have. I just never got into the habit of it. We’re a family of foodies and my son and wife have gotten me into watching a little bit of Top Chef. When the chefs in the show start getting into little catfights, I don’t give a shit. So I sit there and I’m like, “Oh, that’s how you reduce that sauce.” If something is really worth watching and I hear that from enough people I trust, eventually I’ll get the DVDs and watch it. The Sopranos, Deadwood, it’s great. I tried Mad Men, but it just wasn’t for me.

The Wire is watched around the world, you’re invited to conferences around the world, you’re winning awards, and there is one adjective that has been so often used in talking about you work: “influential”. Is it?

Nobody in Hollywood wants to be in business with me because of The Wire. I would’ve loved to be David Chase [creator of The Sopranos], who had great ratings from the jump. I don’t care about people not liking the show or its merits and I don’t care about people critiquing the show, harshly even. That’s called discussion, and the last thing you want to do is to stifle discussion and criticism. But if you can’t address the actual material, and my persona is the only starting point – even if I were the biggest son-of-a-bitch in the world, even if I kicked dogs walking over the street – the ad hominem is a pathetic failure at having an actual discussion.

So, to see John Goodman’s character, for instance, as merely a megaphone for your personal views is to miss the more global point of the discourse …

They were still saying that I was the voice of John Goodman halfway through the show. During the rant I referred to earlier, Goodman says, “Fuck all those other cities, Fuck New York!” and when he gets to San Francisco and he calls it “an overpriced cesspool with hills.” Now, that’s a clue. I think San Francisco is one of the most beautiful places on earth. You embed the clue that the guy is an unreliable narrator, to use the phrase from literature, and somebody will still come along and write, “David Simon believes this.” Is that really the level of discussion, is that where we’re going? So you can’t read the article anymore and you think, “This guy’s an idiot … but there’s a lot of idiots.”

The interview was originally published in 032c Issue 20 (Winter 2010/2011).